The following is a reply to Toby Ord’s “Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian” (2013). Ord’s essay seems to have been quite influential, and is often cited as an essay that makes strong points against negative utilitarianism.

While a number of critical replies have already been written, I still think there are many problematic things in Ord’s essay that have not yet been properly criticized. For example, the essay does not only make misleading and problematic claims about negative utilitarianism, but also about the moral and political views of Karl Popper. Thus, I feel a thorough point-by-point reply is called for. Quotes from Ord’s essay are written in a blue font.

A less than charitable introduction

Introduction

I have been surprised to see that some of my friends and acquaintances in the effective altruism community identify as Negative Utilitarians. Negative Utilitarianism (NU) is treated as a non-starter in mainstream philosophical circles, and to the best of my knowledge has never been supported by any mainstream philosopher, living or dead. This is quite an amazing lack of support: one can usually find philosophers who support any named position. On considering the theory in some detail, I cannot help but agree that the philosophical community has got this one right.

First, we should be clear that philosophical views ought to be evaluated primarily on the basis of their own merits and supporting arguments and counterarguments — not on their number of followers. Of course, I am not saying that Ord claims otherwise, yet starting a critique of NU by invoking a (purported) consensus against it may nonetheless serve to place NU in an unfairly bad light, and introducing a critique of a view in this way is arguably at odds with the principle of charity. I am sure that Ord himself would agree that academic neglect of a given view or issue is not itself a strong reason to dismiss that view or issue. After all, Ord and colleagues have often argued that the academic community is generally quite bad at focusing on what is most important (see e.g. Ord, 2020, p. 58). And there could be various reasons explaining why NU and similar views have not received the attention that they deserve (e.g. because those views are disturbingly dark, and because expressing such views could be bad for one’s social life and career, cf. Knutsson, 2020; Vinding, 2020, ch. 7).

Second, as others have pointed out, the purported lack of support for NU in the “philosophical community” is simply inaccurate. Here is Simon Knutsson pointing to a number of academics who have endorsed negative utilitarian views, or views that these academics themselves have described as resembling NU:

NU has been supported by mainstream philosophers: Gustaf Arrhenius and Krister Bykvist say that they “reveal” themselves “as members of the negative utilitarian family.” J. W. N. Watkins describes himself as “sort of negative utilitarian.” Clark Wolf defends what he calls ‘negative critical level utilitarianism’ for social and population choices. The principle says that “population choices should be guided by an aim to minimize suffering and deprivation.” Thomas Metzinger proposes the ‘principle of negative utilitarianism.’ Ingemar Hedenius held a view similar to negative utilitarianism. According to his form of consequentialism, some sufferings cannot be counterbalanced by goods. Joseph Mendola proposes a modification of utilitarianism that “resembles … negative utilitarianism.” His principle prescribes that “we are to look to the worst possible outcomes in evaluating actions and institutions” and “to ameliorate the condition of the worst-off moment of phenomenal experience in the world.”

For additional remarks on this matter, see NU FAQ, 2.2.14; Vinding, 2020, 8.17.

But as we shall see next, Ord’s opening remarks about negative utilitarianism in particular are actually not all that relevant to the main issue he sets out to discuss, which is instead the moral asymmetry between happiness and suffering.

What Ord argues against: The moral asymmetry in NU

I’m therefore writing this note to those of you who are tempted by NU to show you some of the unsatisfactory consequences it has, and to try to convince you that it is indeed a non-starter.

NU comes in several flavours, which I will outline later, but the basic thrust is that an act is morally right if and only if it leads to less suffering than any available alternative. Unlike Classical Utilitarianism, positive experiences such as pleasure or happiness are either given no weight, or at least a lot less weight. (In what follows, I use the word ‘happiness’ to stand in for whatever aspects of life might be thought to have positive value).

I shall not argue against the Utilitarian part of this. I am very sympathetic towards Utilitarianism, carefully construed. While it is not widely accepted, it has a very strong intellectual tradition and is supported in various forms by some of the most prominent philosophers alive and dead. What I shall argue against is the asymmetry between suffering and happiness in NU, which is something that I do not think can be plausibly and coherently maintained.

Note that this is a Motte and Bailey of sorts. First, Ord makes strong claims about NU (which turn out to be inaccurate claims, cf. Knutsson’s quote above), but he then moves on to reveal that the main position he seeks to criticize is in fact the asymmetry between suffering and happiness. And what Ord fails to mention here is that such an asymmetry — the core view that he is about to criticize — has indeed been widely supported by mainstream philosophers, and hence it likewise has a “very strong intellectual tradition”.

In addition to the philosophers mentioned above by Knutsson, philosophers who have defended an asymmetry between suffering and happiness include Epicurus, Arthur Schopenhauer, W. D. Ross, G. E. Moore, Karl Popper (see e.g. Mathison, 2018, 2.5), Jamie Mayerfeld, Richard Ryder, and some philosophers in the tradition of Buddhist ethics.

Indeed, support for a moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness appears to be more common in academic philosophy than does support for a strict symmetry that would imply that it is just as morally important to turn unproblematic states into intense happiness as it is to relieve (“similarly”) intense suffering (cf. Knutsson, 2016). (Some version of an evaluative and moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness also seems more popular among the broader population, cf. Tomasik, 2015b; Future of Life Institute, 2017; Caviola et al., 2022.)

In sum, many philosophers support the “asymmetry between suffering and happiness in NU” (the aspect that Ord sets out to criticize), while they reject the utilitarian part of NU (the aspect that he sets aside). Thus, if Ord’s aim is indeed to “argue against … the asymmetry between suffering and happiness in NU”, then his opening remarks concerning the level of support for strict NU appear less relevant than would some remarks about the level of support for the asymmetry that he seeks to dispute.

Misleading remarks about the history of NU ideas

History

The idea of NU appears to mainly trace back to some remarks made by Karl Popper in The Open Society and Its Enemies.

I think this is a misleading claim, for two reasons. First, NU, and especially the moral asymmetry that Ord seeks to criticize, has historical roots that are much deeper than Karl Popper or any other modern thinker. For example, as noted above, an axiological asymmetry between suffering and happiness seems widely endorsed in the tradition of Buddhist ethics, and the views defended by Epicurus likewise entail such an asymmetry. Many similar threads can be identified in the tradition of philosophical pessimism, which has deep roots as well. (See also the writings of 19th-century philosopher Edmund Gurney.)

Second, the claim that NU appears to mainly trace back to “some remarks made by Karl Popper” seems misleading given that the moral importance of suffering was not merely something Popper endorsed in “some remarks”, but instead very much at the heart of his moral view, and something he emphasized repeatedly throughout his work.

For example, in The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945), Popper wrote that “all moral urgency has its basis in the urgency of suffering or pain” (p. 548), and that “the fight against suffering must be considered a duty, while the right to care for the happiness of others must be considered a privilege confined to the close circle of their friends. … Pain, suffering, injustice, and their prevention, these are the eternal problems of public morals, the ‘agenda’ of public policy …” (p. 442).

Likewise, in his book Conjectures and Refutations (1963), he wrote: “Do not allow your dreams of a beautiful world to lure you away from the claims of men who suffer here and now” (p. 485). He went on to write: “In brief, it is my thesis that human misery is the most urgent problem of a rational public policy and that happiness is not such a problem” (p. 485). And: “we should never attempt to balance anybody’s misery against somebody else’s happiness” (pp. 485-486). (For more, see Popper, 1963, ch. 18; Shearmur, 1996, ch. 4.)

A misreading of Popper

Ord continues with (one of the many) remarks Karl Popper made that support a moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness:

[Popper:] ‘there is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between suffering and happiness, or between pain and pleasure… In my opinion human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway. A further criticism of the Utilitarian formula ‘Maximize pleasure’ is that it assumes a continuous pleasure-pain scale which allows us to treat degrees of pain as negative degrees of pleasure. But, from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure, and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure. Instead of the greatest happiness for the greatest number, one should demand, more modestly, the least amount of avoidable suffering for all…’

Ord again:

The context of these remarks was an attempt by Popper to construct three practical principles for public policy. He places minimising suffering alongside the principles of tolerating the tolerant and resisting tyranny.

(Those who are not particularly interested in the moral and political views of Karl Popper may prefer to skip the next few paragraphs.)

I think it is misleading to claim that the context of these remarks was an attempt to construct practical principles for public policy, for at least two reasons. First, the passage that Ord quotes above comes from a footnote to Chapter 9 in Popper’s Open Society and Its Enemies, while the three principles that Ord refers to are outlined elsewhere (in Note 6 to Chapter 5), and those principles are not in any way invoked in or around the text quoted from Popper above. That is, Popper’s quote above concerns the moral importance of suffering, and clearly supports a strong moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness in general. There is nothing in those remarks or in the surrounding text that suggests that these claims should amount to a mere practical claim or principle, or that they should apply only in the sphere of public policy (cf. Ord’s interpretation below). Such an interpretation has no basis in Popper’s text.

Second, the way Popper himself describes the three principles that Ord refers to (i.e. those found in Note 6 to Chapter 5) seems to me rather different from Ord’s description of them as just being “practical principles for public policy”. What Popper wrote, in his own words, was that these principles seemed to him “the most important principles of humanitarian and equalitarian ethics” (emphasis mine) (Popper, 1945, p. 548). And it seems even less accurate, in light of this description, to claim that Popper’s principle regarding the overriding urgency of suffering “was just meant as one of three rules of thumb” (as Ord writes below).

Finally, while Popper did place the minimization of suffering “alongside” these two other principles in the sense of listing them together, it seems clear that he did not place it “alongside” these other principles in terms of granting them equal status. After all, many of Popper’s quotes strongly imply that suffering has unrivaled moral priority, such as when he writes that “all moral urgency has its basis in the urgency of suffering or pain”, and that “human misery is the most urgent problem of a rational public policy” (Popper, 1945, p. 548; 1963, p. 485). And Popper indeed explicitly writes that he regards his third principle — “the fight against tyranny” — as essentially amounting to “the attempt to safeguard the other principles [i.e. the reduction of suffering and upholding tolerance toward the tolerant]”, which in effect renders the third principle purely instrumental to the other two principles (Popper, 1945, p. 549).

The world destruction argument

R. N. Smart wrote a response in which he christened the principle ‘Negative Utilitarianism’ and showed a major unattractive consequence. A thorough going [sic] Negative Utilitarian would support the destruction of the world (even by violent means) as the suffering involved would be small compared to the suffering in everyday life in the world. J. J. C. Smart (the brother of R. N.) makes the same argument in Utilitarianism: For and Against. The reason most of us see to support the continuation of humanity is that there is some kind of positive value in it, but this kind of response is not available to a hardline Negative Utilitarian who is simply trying to minimise suffering.

It has been disputed whether this supposed practical implication of NU is indeed an implication of NU, and whether NU is more likely than other consequentialist views to justify violence and killing (Knutsson, 2021a). Indeed, various proponents of NU have argued that the world destruction implication does not follow (see e.g. NU FAQ, 3.2; Tomasik, 2011; Ajantaival, 2022).

As Teo Ajantaival argues, it is important to distinguish purely theoretical implications from the practical implications of a given view. And in terms of theoretical implications, one can argue that other consequentialist views — i.e. views that do allow purported positive goods to “outweigh” extreme suffering — have implications that are much worse than those of NU. For example, classical utilitarianism implies that it would be a net benefit to create arbitrarily large amounts of extreme suffering in order to make a “sufficiently” large number of very happy individuals even happier.

It is also worth noting that the implication that Ord claims would follow from NU is not, in any case, an implication that need follow from a moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness. Such an asymmetry can be — and often has been — combined with various other values that would prohibit attempts to destroy the world (see e.g. Wolf, 1997, VIII; Mayerfeld, 1999, p. 159; Vinding, 2020, 8.1).

Another misreading of Popper

Popper responded to R. N. Smart by saying that he supposed Smart’s unpleasant conclusion would indeed follow from accepting Minimise Suffering as a criterion of right action, but that it was never meant this way. It was just meant as one of three rules of thumb, and only meant for public policy, not individual action. [Ord cites: Karl Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies, vol. 2. Addenda I. 13.]

I believe this reading of Popper is wrong, and in some sense an inversion of Popper’s view. (Again, those who are not particularly interested in the views of Karl Popper may prefer to skip the next couple of paragraphs.)

I think it is clear from Popper’s writings that he did in fact endorse a general duty to reduce suffering, such as when he wrote that “suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help” and that “the fight against suffering must be considered a duty” (Popper, 1945, p. 442, 602). In making these statements, Popper nowhere indicates that this moral duty and appeal for help should fail to extend to our individual actions (nor does Ord’s citation in any way support such an interpretation).

Indeed, Popper’s point regarding public policy was in some sense the opposite of what Ord implies: Popper not only maintained that suffering makes a “direct moral appeal for help” and that its reduction “must be considered a duty”, but he further maintained that it deserved to be raised to a foremost aim of public policy (Popper, 1945, p. 442, 501, 548; 1963, p. 465, 485). In other words, Popper granted the reduction of suffering an even higher status than that of a generic moral precept. Far from seeing the reduction of suffering as “just a rule of thumb”, Popper argued that suffering has unique moral urgency and importance, which was why he regarded pain and suffering, along with injustice, as “the eternal problems of public morals, the ‘agenda’ of public policy” (see Popper, 1945, vol II, ch. 24; 1963, ch. 18).

In contrast, Popper argued that the promotion of happiness did not deserve to be elevated to a public policy aim, and that it should instead “be left, in the main, to private initiative” (Popper, 1945, p. 442; 1963, p. 465).

Not a negative utilitarian — but still a supporter of a strong moral asymmetry

Popper was not, therefore, a Negative Utilitarian (nor any other kind of Utilitarian).

That is correct. But he clearly did endorse a moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness, which, again, was the aspect of NU that Ord said he aimed to criticize, whereas the aspect that Popper rejected was precisely the “Utilitarian” part that Ord set aside.

This has pretty much been the end of the debate in the academic philosophical literature about NU. Its main role in the academy is as a position that is sometimes mentioned as a rival to Classical Utilitarianism in introductory classes, then shown to be open to severe critiques and discarded.

These claims again give a misleading impression of the support for NU in academia (cf. the academic philosophers and views mentioned by Knutsson above), and the claims again focus on NU rather than the moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness that Ord aimed to criticize. This asymmetry has been defended at length and in various forms in the academic literature since Popper and Smart wrote about these issues (see e.g. Mayerfeld, 1996; 1999; Wolf, 1996; 1997; 2004; Benatar, 1997; 2006).

Different strains of NU and some literature that supports them

Types of Negative Utilitarianism

Before outlining my objections to NU I need to distinguish between several different strengths [sic; I believe Ord meant to write “strains”] of NU, since they each have some unique problems, as well as some problems in common.

I take all forms of NU to combine some form of consequentialism (i.e. that the right act is the one that leads to the best outcome) with an axiology (i.e. a definition of which outcomes are better than which others). I stratify the types of NU by how much emphasis its axiology places on suffering over happiness.

Absolute NU

Only suffering counts.

Lexical NU

Suffering and happiness both count, but no amount of happiness (regardless of how great) can outweigh any amount of suffering (no matter how small).

Lexical Threshold NU

Suffering and happiness both count, but there is some amount of suffering that no amount of happiness can outweigh.

Weak NU

Suffering and happiness both count, but suffering counts more. There is an exchange rate between suffering and happiness or perhaps some nonlinear function which shows how much happiness would be required to outweigh any given amount of suffering.

I think it would have been good (and in keeping with standard academic norms) if Ord had referred to some sources that defend these views or views that are very similar. Below are a number of such sources, many of which were published before Ord wrote his essay in 2013.

The following sources explore and defend views that are similar to “Absolute NU” at the level of their underlying axiology (i.e. theory of value): Schopenhauer, 1819; 1851; Fehige, 1998; Breyer, 2015. In addition to such formally published works, there are also various essays published online that defend similar views. These include Geinster, 1998; 2012; NU FAQ (2015); Gloor, 2017; Ajantaival, 2021/2022. (I am not saying that Ord should have referenced any of these informally published sources, most of which were published after 2013 anyway, but I include them here for completeness, and because I think they add substantially to the formally published sources.)

Publications that defend what Ord calls “Lexical NU” (particularly in the domain of population ethics) include Wolf, 1996; 1997; 2004.

Views similar to what Ord calls “Lexical Threshold NU” have been defended in Gurney, 1887, ch. 4; Mendola, 1990; Ryder, 2006, pp. 73-80; Leighton, 2011, ch. 9; Tomasik, 2015a; Vinding, 2020, ch. 4-5.

Sources that defend axiological views similar to what Ord defines as “Weak NU” include Arrhenius & Bykvist, 1995; Mayerfeld, 1999; Mathison, 2018.

A restricted definition of an impartial view

The above are all types of true NU. However some people with Negative Utilitarian intuitions don’t support any of them. They instead agree that there is a theoretical symmetry between suffering and happiness and thus support the theory of Classical Utilitarianism. However, in a wide variety of practical cases they agree with the Negative Utilitarians in the moral focus on suffering. I’ll outline two forms of this:

Strong Practically-Negative Utilitarianism

Classical Utilitarianism with the empirical belief that suffering outweighs happiness in all or most human lives.

Weak Practically-Negative Utilitarianism

Classical Utilitarianism with the empirical belief that it in many common cases it [sic] is more effective to focus on alleviating suffering than on promoting happiness.

It is worth flagging how Ord defines “Strong Practically-Negative Utilitarianism” as being based on “the empirical belief that suffering outweighs happiness in all or most human lives” (emphasis mine). This is a rather narrow belief to base an impartial view on. That is, utilitarianism — whether classical or negative — pertains to all sentient beings whom we can influence, of which existing human lives are but a tiny fraction. Non-human animals constitute the vast majority of existing beings, and existing beings in turn likely represent a small fraction of beings compared to future beings (the majority of whom may well be non-human as well).

Ord defines “Weak Practically-Negative Utilitarianism” in a more impartial way, namely as the view that “in many common cases it is more effective to focus on alleviating suffering” (without any reference to human suffering in particular). And it seems that it would make more sense to define the strong version of this view in a similar way — e.g. as based on the belief that “it is almost always more effective to focus on alleviating suffering”. After all, a classical utilitarian could hold both that “happiness outweighs suffering in most human lives” and hold that it is almost always more effective to focus on the alleviation of suffering (e.g. Peter Singer may be interpreted as expressing such a view here).

Specifically, one could think that we can usually make the greatest difference by helping non-human beings. And even if we were to restrict our focus to humans only (which seems no more justifiable than does, say, an exclusive focus on humans of a certain gender), one could still think that the reduction of suffering is generally more tractable than is the increase of happiness among the majority of humans. Or one could think that we can generally make the greatest difference (among humans) by helping the most miserable people, even if they only represent a minority.

Arguing in good faith

Objections to Negative Utilitarianism

I’ll argue against all four theoretical forms of NU and also against the first practical form. I won’t argue agains [sic] the weak practical form as I think it is perfectly reasonable and would be supported by almost all Classical Utilitarians. Indeed, I think it is the best way to account for Negative Utilitarian intuitions within a solid theory.

It is always quite difficult to argue against many forms of a view simultaneously as there is normally some kind of change that can be made to create a new form which the argument doesn’t engage with. Sometimes this change is to a legitimate and independently motivated new version of the view. Sometimes it is just adding an epicycle.

In this essay, I’m trying to argue in good faith to help my friends see some serious problems with their views, so I hope that the reader (whether friend or stranger) will take the argument in this way. The point is not whether there is some kind of acrobatics or extreme bullet biting that would enable one to avoid each of the arguments I give, but whether they make you think that a once promising theory is looking increasingly like a bad thing to bet the future of our world on.

While Ord writes that he is trying to argue in good faith, I think there are many aspects of his reply that fall short of that standard. I have already noted how his introducing NU with (inaccurate) claims about its lack of support in academic circles can seem quite at odds with the principle of charity and good-faith argumentation. But more glaring examples of less-than-good-faith argumentation follow below, such as when Ord shortly claims that one would have to be “crazy” to accept the implications of NU.

Status quo bias and framing the NU choice as a “threat”

Absolute NU — The indifference argument

Absolute NU is completely indifferent to happiness (over and above any merely instrumental effects it has on reducing suffering). Suppose there were a world that consisted of a thriving utopia, filled with love, excitement, and joy of the highest degree, with no trace of suffering. One day this world is at threat of losing almost all of its happiness. If this threat comes to pass, almost all the happiness of this world will be extinguished. To borrow from Parfit’s memorable example, they will be reduced to a state where their only mild pleasures will be listening to muzak and eating potatoes. You alone have the power to decide whether this threat comes to pass. As an Absolute Negative Utilitarian, you are indifferent between these outcomes, so you decide arbitrarily to have it lose almost all of its overflowing happiness and be reduced to the world of muzak and potatoes.

It is important to clarify that in the thought experiment Ord is proposing here, nobody would be experiencing even the mildest suffering due to the non-existence of happiness. After all, if suffering did ensue from the “no happiness” choice, then Absolute NU would not endorse it. This is worth clarifying since it is quite intuitive to imagine that the second world Ord describes (a world of “listening to muzak and eating potatoes”) would entail some bothersome disappointment about the lost happiness, although that would be contrary to the premise of the thought experiment. Such misinterpretations are only made more intuitive by the framing of this happiness-free prospect as a “threat”, a “loss”, and a world that is “reduced” — words that usually connote something that is positively hurtful. And the misinterpretation is also made intuitive by the fact that, in our world, “listening to muzak and potatoes” is unlikely to involve a perfectly unproblematic and unbothered experience.

To avoid such misunderstandings, it is important to control for any potential status quo bias we may have when evaluating this thought experiment, as well as to state the thought experiment in terms that render it unmistakably clear that none of the conditions involve any problematic experiences whatsoever. To avoid the status quo bias, we should assume that there is no world to begin with, and that our choice will be to either create the world of extreme bliss that Ord describes, or to create a world of perfectly untroubled beings who experience no aversive experiences whatsoever.

When phrased in this way, it is not clear that there would be anything wrong with choosing the untroubled world that is devoid of any aversive experiences or cravings, and in which nobody is the least bothered by the non-existence of intense pleasure.

“You would have to be crazy”

I think this example pretty much speaks for itself. You would have to be crazy to choose the world devoid of happiness, but Absolute NU says this is just as good and doesn’t mind whether you choose it or not. This outcome would be catastrophically worse for all individuals, making Absolute NU a devastatingly callous theory.

As hinted above, the claim that “you would have to be crazy” to endorse this implication of Absolute NU seems in tension with Ord’s claim about trying to argue in good faith. Indeed, I suspect that Ord would also consider it uncharitable and less than good-faith argumentation if anyone claimed that “you would have to be crazy” to accept a given implication of his favored view.

Such claims aside, it is difficult to see how the choice of the unproblematic world is “catastrophically worse for all individuals”, considering that the individuals in this world are all perfectly untroubled and unbothered by the absence of extreme bliss.

As for the notion that Absolute NU is a “devastatingly callous theory”, I am inclined to agree with the following response from David Pearce: “No: NU is an unsurpassably compassionate theory. You are ‘callous’ only if you are indifferent to someone’s suffering, not if you don’t act to amplify the well-being of the already happy or act to create happiness de novo”.

Assuming that “pretty much all” negative utilitarians would move on

As this argument only affects Absolute NU, I imagine that pretty much all people of a Negative Utilitarian persuasion who hear it would at least move to Lexical NU, which accepts that happiness can at least break ties, avoiding this argument. (This is analogous to the case of distributional principles in ethics, where all supporters of maximin have moved to leximin.)

Ord’s assumption that “pretty much all people of a Negative Utilitarian persuasion” would give up on Absolute NU in light of his objection above seems unlikely to be true. Those who endorse Buddhist axiologies that see the cessation of suffering as the only good, as well as Epicureans and anyone else who endorses a minimalist axiology, would all disagree that happiness has any positive intrinsic value (i.e. independent value in causal isolation).

When we are careful to distinguish the instrumental value of happiness from its purported intrinsic value — such as by clarifying that the happiness in the thought experiment above occurs in isolated matrix lives that have no beneficial effects on others — and when we control for status quo bias, by considering scenarios from a neutral starting point rather than from the perspective of one of the worlds in question, it is not clear that the argument that Ord brings up has much force against Absolute NU. (See also NU FAQ, 2.2.2.)

The pinprick argument: Status quo bias and destruction revisited

Lexical NU — The pinprick argument

Lexical NU is willing to sacrifice arbitrarily large amounts of happiness to avoid a single pinprick. It therefore succumbs to examples very similar to the one above. For example, suppose one of the lucky people in the utopia of love, excitement, and joy, were to have a tiny amount of suffering amidst their sea of happiness — in a moment of carelessness in their heavenly garden, they prick their thumb on a rose thorn. It is only a very small pain, and they find that it is already outweighed by the pleasure of smelling that very rose. Lexical NU says that it is so important to avoid that pinprick that it would be obligatory to destroy all that is good about their world and force the inhabitants down to the muzak and potatoes lives, if we could thereby avoid that pinprick.

If the “small pain” in this thought experiment involves an experience-moment that is overall dominated by suffering, then it is worth noting that this thought experiment does indeed involve a real (if fleeting) victim, namely that experience-moment of suffering. And it is far from trivial to claim that the suffering of that experience-moment is “outweighed” by the pleasure or the experiential evaluation found in another experience-moment.

Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, we again need to control for the status quo bias, since Ord once again frames the thought experiment such that we start out in one of the two conditions under consideration, and such that choosing the suffering-free outcome requires us — according to Ord — to “destroy all that is good” and “force” people down. If we frame the thought experiment in a neutral way, this would not be the case (cf. Bostrom & Ord, 2006).

On the contrary, if we adopt a neutral starting point (e.g. a world with no existing individuals), one can argue that the only scenario that involves “forcing someone down” is the world that entails an experience-moment dominated by suffering. Only this world contains a victim who suffers, whereas the other world, in which everyone is perfectly untroubled, involves no suffering and no victims. (A similar reply to Ord’s argument is found in Vinding, 2020, 8.9.)

Note also that preference-based versions of NU would not necessarily say that it would be better to “sacrifice arbitrarily large amounts of happiness” in order to avoid a small pain. For if existing individuals preferred not to lose the happiness in question, then losing it could well amount to a greater preference frustration overall. Yet such views would still agree that it would be better not to create the pain and these preferences in the first place, which is another reason why the framing of the thought experiment might matter greatly (i.e. on some views it makes a substantive difference whether we are talking about populations or preferences that already exist versus merely potential ones).

Indeed, preference-based views — as well as commonsense intuitions — may even strongly prefer the untroubled condition if we invert the status quo in Ord’s thought experiment, by assuming that everyone already experiences and prefers undisturbed contentment, and that this peaceful contentment would be “destroyed” by the addition of a small pain and intense bliss that nobody asked for or wanted.

Once again, this outcome would be catastrophically worse for all the individuals (including the one whose suffering we are trying to avoid!). It is not possible to construe this as respectful of the interests of individuals. Lexical NU is thus also a devastatingly callous theory.

It seems that one could just as well argue for the opposite view: choosing the world in which everyone is perfectly untroubled is arguably not harmful or worse for anyone. (Again, this conclusion would be implied by Buddhist and Epicurean views according to which untroubled contentment is as good as — and perhaps even better than — intense pleasure.)

In contrast, choosing the world that contains an experience-moment of suffering does entail forcing someone down to a problematic state, and this individual state is clearly worse off compared to all of the states found in the unproblematic scenario. One can thus argue that choosing the perfectly untroubled scenario is more respectful to the interests of individuals — and more compassionate — than is forcing an experience-moment to suffer.

A misleading claim about “sacrificing everything of value”

A natural retreat for the proponent of Lexical NU is to accept that a pinprick is too small an amount to suffering [sic] to warrant sacrificing everything of value to avoid. They can instead hold that there is at least some level of suffering where this would make sense.

As we have seen, proponents of Absolute or Lexical NU have many possible replies available to the arguments Ord has provided so far, and hence they need not feel much of a pull, if any, to “retreat” to a weaker version of their views in light of Ord’s arguments.

Moreover, Ord’s claim about “sacrificing everything of value” to avoid a small amount of suffering is not something that anyone who endorses Absolute or Lexical NU would agree with. First of all because what Ord refers to as “everything of value” (i.e. that which would be “sacrificed”) is something like “happiness whose absence causes no problem”. Yet Absolute NU would assign no value whatsoever to such “unneeded happiness”, while Lexical NU would assign it only second-rate (i.e. lexically inferior) value compared to the greater value of reducing suffering — a value that would indeed be attained through the “sacrifice” that Ord proposes.

Furthermore, proponents of NU would also reject Ord’s claim about “sacrificing everything of value” in terms of how this claim is likely to be interpreted at an intuitive and practical level. In particular, proponents of Absolute and Lexical NU would reject the “sacrificing everything of value” claim in the sense that these views can in practice recognize the significant positive roles served by things such as knowledge, motivation, and autonomy. These things are all “of value” in a very real sense according to NU. And while the value of these entities is purely instrumental by the lights of NU, it is still often the case that the instrumental value of these things is much greater than the disvalue of a single mild state of suffering (in terms of how much suffering they enable us to avert). This is another important sense in which Absolute and Lexical NU do not imply that it is worth “sacrificing everything of value” to avoid a small amount of suffering. In practice, these views will often recommend great sacrifices for the sake of creating durable resources of instrumental value.

To be sure, Ord’s thought experiment is a purely theoretical one, and so it disregards all entities that merely have instrumental value, or “value in practice”. But the point is that our intuitions probably do not disregard such value, and hence even someone who strongly endorses NU would likely agree that a small amount of suffering does not “warrant sacrificing everything of value” (in terms of how that statement is likely to be interpreted in the absence of further clarification). By analogy, a classical utilitarian would probably also object and be eager to clarify if they were accused of being willing to sacrifice all justice, truth, and beauty for the sake of avoiding the tiniest of pain. In general, it is important to ensure that thought experiments do not bring in confounding issues and intuitions.

Questioning intuitions about aggregation

Lexical Threshold NU — The continuity argument

As far as I understand, David Pearce supports a version of Lexical Threshold NU:

[Pearce:] ’It [i.e. NU] stems instead from a deep sense of compassion at the sheer scale and intensity of suffering in the world. No amount of happiness or fun enjoyed by some organisms can notionally justify the indescribable horrors of Auschwitz. Nor can it outweigh the sporadic frightfulness of pain and despair that occurs every second of every day.’

I share David’s sense of horror at Auschwitz. An estimated 1.3 million people died there amidst unfathomable emotional and physical suffering. I can also see that there is a vast amount of suffering in the world every day, though my access to this second fact is more through a process of calculation rather than raw horror.

I don’t agree though about whether these quantities of suffering, vast though they are, can be outweighed by the positive side of human experience. One problem with making headway in such a debate is that our intuitions become pretty useless. There are 7 billion people in the world today and it appears to me that the average life has a non-negligible amount positive [sic] wellbeing (and has net positive moral value if you think those things are different). I thus think there is a lot of value worth of happiness in the world.

Is it enough to make a single year outweigh the horrors of Auschwitz? I don’t have a strong intuition, but I think this is mainly because I’m comparing the suffering of millions with the quality of life of billions. This is a hard thing to have a proper intuition about, since our internal representations of these quantities are basically the same: we find it hard to feel differently about the suffering of one million or the suffering of one billion. This makes me distrust my intuitions, especially as this comes up all the time with millions and billions, so doesn’t [sic] seem to be a particularly moral feature of my intuition. I’d like to divide each number by one million and make the simplified comparison, but I gather that David Pearce thinks that is not an analogous question.

Ord appears to invoke the unreliability of human intuitions when it comes to large numbers. But large numbers (of happy experiences) are quite irrelevant according to views such as Absolute NU and Lexical NU — which Ord has by no means refuted — since a large number of something that has no or lexically inferior (intrinsic) value will still just have no or lexically inferior (intrinsic) value.

I assume Ord’s point is that if we grant that some amount of happiness can outweigh some amount of suffering (which I submit he has not made a compelling case for), then we cannot trust our intuitions as to whether vast amounts of happiness can likewise outweigh extreme suffering. But a similar argument could be made against an intuition that Ord’s line of reasoning appears to implicitly rest on, namely the intuition that many instances of a given value entity can necessarily be “added up” so as to “outweigh” or have greater (dis)value than some wholly different value entity. Why should this intuition be reliable or valid? After all, there is little a priori reason to think that we should trust that (to many people highly counterintuitive) intuition of aggregation any more than we should trust, say, our intuitions regarding large numbers.

It is also worth flagging that the scope of Ord’s discussion again seems unjustifiably restricted, in that he only focuses on “human experience”, thereby neglecting the vast majority of sentient beings on the planet, namely non-human beings, who generally seem much worse off than humans. If one includes factory farming and wild-animal suffering in one’s assessments, the picture seems to skew (even) more heavily toward pessimistic conclusions. (A case for thinking that most people’s values would imply a pessimistic conclusion even when we restrict the focus to humans only is found in Contestabile, 2022.)

Inaccurate claims about lexical views

However, there is an argument which allows us to make serious headway in resolving the disagreement. If you believe in Lexical Threshold NU, i.e. that there are amounts of suffering that cannot be outweighed by any amount of happiness, then you have to believe in a very strange discontinuity in suffering or happiness. You have to believe either that there are two very similar levels of intensity of suffering such that the slightly more intense suffering is infinitely worse, or that there is a number of pinpricks (greater than or equal to one) such that adding another pinprick makes things infinitely worse, or that there is a tiny amount of value such that there is no amount of happiness which could improve the world by that level of value.

Ord’s claims about what “you have to believe” upon endorsing a lexical view are simply not true. In particular, the claims about small experiential changes that make things “infinitely worse” need not be endorsed by proponents of lexicality. Nor does a proponent of lexicality need to endorse a sharp threshold at which lexicality suddenly kicks in. (See also here and here, as well as Knutsson, 2021b.)

Ord seems to implicitly assume a number of things when he makes these claims — e.g. that value is to be represented with real numbers, and that these real numbers can straightforwardly be added to yield a sum of value. But these assumptions are not obviously plausible, and they can reasonably be questioned.

Indeed, to assume that the value of all value entities can be represented with real numbers, and to further assume that this value must add up linearly, simply begs the question against lexical views (since these assumptions trivially rule out lexicality). This means that one cannot simply make these assumptions from the outset when arguing against lexical views. Instead, someone who argues against lexicality with reference to these assumptions would need to argue why these assumptions about real numbers and linear addition are plausible to begin with.

The argument goes like this. We can imagine a long sequence of levels of intensity of suffering from extreme agony down to a pinprick, each of which differs from the one before it by a barely detectable amount. If we want to avoid the discontinuity in the badness of the intensity of suffering, then the suffering of a million people at the extreme agony intensity level must be only finitely many times as bad as the suffering of a million people at the next intensity level down, which is only finitely many times as bad as the suffering at the next level, and so on all the way down to the level of the pinprick. This implies that suffering at the very high intensity level is only finitely times [sic] worse than the suffering at the pinprick level.

Again, Ord here seems to assume that value is to be represented with real numbers, such as when he talks about some suffering being only “finitely many times as bad” as some other suffering. As Simon Knutsson notes, there is no need for someone with a lexical view to endorse any of these claims about some suffering being finitely or infinitely worse than something else:

What a Lexical Threshold NU can say is merely that there is some suffering that is worse than some other things, no matter how many of them there are. To say that the more important suffering is thereby “infinitely worse” is an extra step that the Lexical Threshold NU need not agree with.

Ord continues:

Moreover unless, [sic] there is to be a case where n+1 people getting a pinprick is infinitely worse than n people getting a pinprick (for n greater than or equal to 1), we can run a similar argument moving from a million people receiving a pinprick down to a single person and show that the former must only be finitely many times worse than the latter. We thus get the conclusion that while a million people in agony is terrible, it is still only finitely times as bad as a single person receiving a pinprick.

Again, Ord’s conclusion that “a million people in agony is only finitely times as bad as a single person receiving a pinprick [i.e. a mild pain, cf. the pitfalls of focusing on stimulus]” has by no means been established by his argument above. Specifically, Ord has not established that it is plausible to add up mild pains such that a large number of them have greater disvalue than a single state of agony. He simply assumes linear addition with real numbers, which is precisely the kind of framework that someone with a lexical view would dispute.

An argument based on questionable premises

Because we are not discussing strict Lexical NU, we know that the badness of a single person suffering a single pinprick can be outweighed by some amount of happiness.

I would again disagree with Ord’s claim that “we know” that mild suffering can be outweighed by some amount of happiness. I do not think Ord has made a compelling case for thinking that happiness has independent value that can outweigh suffering — i.e. that happiness can outweigh suffering even if it occurs in isolated matrix lives that have no positive roles for others.

While it is obviously worthwhile to endure some discomfort in order to secure a state of happiness that in turn reduces even greater discomfort, it is much less clear whether this is also the case when the absence of the happiness in question implies no problem whatsoever.

For concreteness, let’s imagine that the happiness of a happy year of life with no suffering is enough to outweigh a pinprick (it seems implausible to reject this, but if you do, then choose some other example). It follows that the goodness of stopping a million people suffering in agony is only finitely many times as good as a happy year of life.

Once again, a viable alternative to “choosing some other example” of happiness that independently outweighs pain is to reject the notion that (isolated) happiness can outweigh pain in the first place. Likewise, Ord’s claim about one thing being “only finitely many times as good” as another is not a claim that one needs to accept, nor a claim that Ord has established (i.e. the use of real numbers to represent value has not been defended).

Now we can build upwards again. Unless there is a tiny amount of value such that no amount of additional happiness can ever be worth that amount of value, then we can imagine an increasing chain of valuable states of nature, starting with a happy year of life and ending with something X times better (for any X), which proceeds by tiny steps of value. Since we can always add enough happiness to move through this progression, there must be an amount of happiness X times better than a year of a happy life. There must therefore be an amount of happiness so valuable that it is more valuable than avoiding a million people being in extreme agony, contradicting Lexical Threshold NU.

These statements continue to rest on the unargued and questionable assumption that we have to represent value with real numbers.

Lexical Threshold NU must therefore accept some kind of discontinuity. Either that there are two very similar levels of intensity of suffering such that the slightly more intense suffering is infinitely worse, or that there is a number of pinpricks (greater than or equal to one) such that adding another pinprick makes things infinitely worse, or that there is a tiny amount of value such that there is no amount of happiness which could improve the world by that level of value.

As noted above, these are not positions that one would need to accept if one endorses a lexical view.

Overlooking other motivations for lexical views

All of these options look very unintuitive to me — especially when we had reason to doubt the intuition about large number cases which originally motivated the Lexical Threshold view.

Cases involving large numbers are not the only or necessarily the strongest cases that motivate or speak in favor of a lexical view. A more compelling case in its favor is arguably the qualitative experiential difference between, say, mild discomfort and intense suffering.

Reasons to modify NU?

However, they [i.e. the supposed discontinuity implications presented by Ord above] are not quite so bad as the earlier problems besetting the advocates of Absolute and Lexical NU. I can imagine someone biting one of these bullets if they really needed to. If so, they should make sure to read the ‘worse-for-everyone’ argument, which is even harder to stomach.

Some proponents of this view [i.e. Lexical Threshold NU] would perhaps instead be tempted to modify their view, so that for any amount of suffering, there is always some amount of happiness that can outweigh it, but that this may be a vast amount of happiness, because suffering matters more from a moral point of view than does happiness. This is the view that I’ve called Weak NU.

Again, I do not think Ord has provided a compelling case for why someone who endorses NU (in any of the variants discussed above) should feel tempted to modify their view, especially since none of the discontinuity implications that he associates with Lexical Threshold NU are in fact necessary features of such lexical views.

Objections that cut both ways

Weak NU — The incoherence argument

A major problem with Weak NU is that it appears to be incoherent. What could it mean for suffering to matter more than happiness?

One could ask a similar question in response to classical utilitarianism (CU). What would it mean for suffering to matter “as much” as happiness? The meaning of this claim is not obvious either.

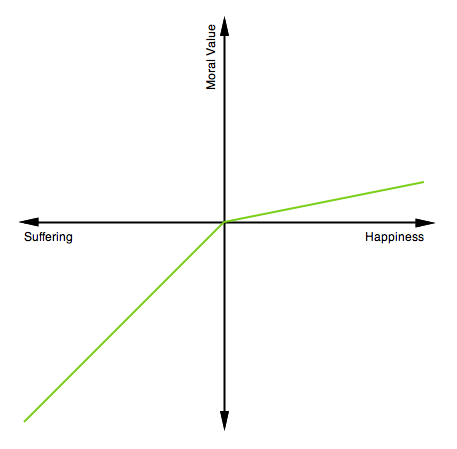

It suggests an image such as this:

But what is the horizontal scale [i.e. the x-axis] supposed to represent? There is no obvious natural unit of suffering or happiness to use. It might be possible to have a consistent scale in the happiness direction and a separate consistent scale in the suffering direction, but it is very unclear how they are both supposed to be on the same scale. This is what would be needed for Weak NU to be a coherent theory and for the diagram to make any sense.

Again, one could make a similar point in response to CU: there is no obvious natural unit of suffering or happiness to use there either. And it is likewise unclear how happiness and suffering are supposed to be “on the same scale” in CU.

Overlooking common candidates to put on the scale

The only things I can think of to put these on the same scale are:

1) How morally good/bad it is.

2) How much it contributes to an individual’s wellbeing.

Classical Utilitarians typically use (1) or (2) to set this scale, and since Classical Utilitarianism holds the moral value of an outcome to be the sum of the individuals’ wellbeing, it doesn’t much matter whether they define this with (1) or (2).

Weak Negative Utilitarians can’t use (1) to set this scale, as otherwise they would have to say that a unit of happiness is just as morally important as a unit of suffering and they would just be Classical Utilitarians.

Ord seems to overlook a number of things that one could put on the x-axis, such as “felt intensity” (or felt “degree”, “depth”, “level”, etc). After all, if one were to grant that the intensity of happiness and the intensity of suffering can be measured on a commensurable intensity scale (itself a questionable assumption), then there would be nothing incoherent about saying that suffering at intensity x is more morally bad — or worse for one’s wellbeing — than happiness at intensity x is good. Indeed, various philosophers have defended such claims (Arrhenius & Bykvist, 1995; Mayerfeld, 1999; Mathison, 2018).

Evaluations of tradeoffs: “The main argument against NU”

I therefore think that the only coherent version of Weak NU is to use (2) to set the common scale between suffering and happiness. However, if they do so, they (along with all other Negative Utilitarians) fall victim to what I think is the main argument against NU.

All forms of NU — The worse-for-everyone argument

In their day to day lives, people make tradeoffs between happiness and suffering. They go to the gym, they work hard in order to buy themselves nicer food, they sprint for the bus to make it to the theatre on time, they read great books and listen to beautiful music when they could instead be focusing on removing suffering from their lives. According to all commonly held theories of wellbeing, such tradeoffs can improve people’s lives.

However, there is a big problem for NU in how it assesses these tradeoffs. Absolute NU and Lexical NU say that no such tradeoff can be moral, as does Lexical Threshold NU if the amount of suffering is greater than its threshold.

First, one can question whether these are really cases of “tradeoffs between happiness and suffering”. After all, one can argue that these activities generally do not involve significant levels of suffering, and that even when they do, they still often serve to reduce suffering overall.

In particular, going to the gym helps to prevent suffering caused by poor physical fitness and feelings of idleness (conversely, it seems unlikely that the aim of minimizing suffering would recommend being physically inactive). Likewise, to the extent that people “work hard in order to buy themselves nicer food”, one can question whether that behavior is indeed mainly driven by the aim of attaining pure pleasure, rather than reducing frustrated preferences and cravings (e.g. tasty foods may relieve gustatory cravings, healthier foods may help keep bad health at bay, and fancy foods may satisfy a need to signal social status).

One could make the same point about “sprinting to make it to the theater on time”, in that failing to make it to the theater on time is likely to trigger unpleasant feelings such as embarrassment (due to other people’s judgments) and regret (due to missing parts of the play). And people may have similar motives for visiting the theater in the first place — e.g. avoiding boredom, avoiding the perception of being a low-status philistine, and avoiding the fear of missing out. The same goes for reading great books and listening to beautiful music: these activities often serve to reduce and prevent unpleasant states, such as feelings of stress and understimulation. (See also Knutsson, 2016; Vinding, 2020, 2.4. An elaborate reply to arguments of the kind that Ord makes above is found in Knutsson, 2022.)

Yet even if we disregard the points made above, and simply grant that people sometimes trade off suffering for pure happiness (i.e. for happiness that does not in turn reduce more unpleasant states), this would still not establish that such tradeoffs are a net benefit or that they are morally right. After all, people make many decisions that seem unjustified and harmful on reflection, such as enjoying short-term indulgences that come at serious costs to themselves in the future (cigarette smoking may be cited as a common example). The same holds true in interpersonal terms: we often spend excessive resources on frivolous things for ourselves when we could have spent them to help others in effective ways. In short, the fact that a behavior is widespread is not a strong reason to consider it net valuable or morally justified.

Finally, Ord is wrong when he claims that “all commonly held theories of wellbeing” hold that it can improve people’s lives to trade suffering for pure happiness. For instance, Buddhist and Epicurean views of wellbeing would disagree that such trades can improve people’s wellbeing, and these views have historically had many adherents, and they continue to have many adherents today. And views of wellbeing that deny that such tradeoffs can improve people’s wellbeing have also been defended in the philosophical literature in modern times (see e.g. Schopenhauer, 1819; 1851; Wolf, 1996; 1997; 2004; Fehige, 1998; for a brief introduction to minimalist views of wellbeing, see Ajantaival, 2023).

Inaccurate claims about Weak NU

Weak NU says that some such tradeoffs can be moral, but if it accepts (2), it must claim that there are tradeoffs which are good for the individual but morally bad overall. For example, if you think that happiness is only a tenth as morally important as suffering, and are using the contribution of happiness and suffering to wellbeing as your measuring stick, then you must think that very many tradeoffs that successfully improve an individual’s wellbeing are morally bad — even if they don’t affect the wellbeing of anyone else.

Again, one can coherently maintain that happiness of intensity x affects a person’s wellbeing less than does suffering of intensity x. Hence, someone who endorses Weak NU need not hold that any improvements to an individual’s wellbeing are morally bad.

Tradeoffs claimed to be in everyone’s interest

Indeed, suppose that there was a situation in which all individuals want to accept 5 wellbeing units of suffering in order to gain 10 wellbeing units of happiness. This would be in everyone’s interest.

It is unclear how Ord interprets “units of suffering” and “units of happiness” in this context. But if we interpret them as, say, “a consciousness-moment of suffering” and a “consciousness-moment of happiness” (an interpretation that is permissible if these units can be moved around in time and still preserve their value), then it is by no means clear that this tradeoff would be “in everyone’s interest”. After all, the five consciousness-moments of suffering would be in an overall harmed state, and it is not obvious how or why these states are supposed to be outweighed by other consciousness-moments that contain happiness (no matter how intense or numerous these instances of happiness may be). Minimalist axiologies would deny that this deal would be in everyone’s — or even anyone’s — interests.

Note also that a confounding factor in this thought experiment could be that the “want” in question — i.e. wanting to gain “10 units of happiness” at the price of “5 units of suffering” — might itself (intuitively) appear to be something that would lead to even greater suffering if frustrated (after all, frustrated wants often lead to suffering in the real world). Thus, to remove this confounding factor, we need to explicitly clarify that the want in question would not lead to any suffering if frustrated (or at least not more than “5 units of suffering”).

Finally, it is worth noting that one could just as well, and perhaps more plausibly, imagine a situation in which all individuals prefer to reject the tradeoffs that a classical utilitarian would have them accept. For instance, the individuals in question may strongly prefer to avoid experiencing “5 units” of intense suffering in order to gain “10 units” of intense pleasure (where these respective units are equivalent according to the classical utilitarian). One could plausibly argue that rejecting the classical utilitarian’s offer would be in everyone’s interest in this case.

However, Weak NU would say that it was impermissible, and that it is instead obligatory to prevent it (for very weak versions of NU with exchange rates less than 2 to 1 a new example can easily be constructed). NU is thus not a theory that supports the overall interests of individuals.

One could make the opposite argument based on the consciousness-moment framing above: the interests of individuals are best supported by not allowing anyone to suffer when the alternative involves no suffering (or at least less suffering).

And in light of the thought experiment above in which people prefer to reject an offer that CU would oblige them to accept, one could plausibly argue that CU is “not a theory that supports the overall interests of individuals”.

Note also that Weak NU would not say that it is “obligatory to prevent” some suboptimal tradeoff in practice, just like CU would not deem it “obligatory to prevent” people from making “CU suboptimal” tradeoffs, since such totalitarian paternalism is likely to have far worse consequences overall. In other words, this is yet another case where it seems necessary to clarify the distinction between theoretical and practical implications.

A question-begging claim about bias

[Weak NU] may support each of the components of their wellbeing in isolation, but it is biased between them in a way that is counter to promoting their wellbeing. In this way it systematically harms people.

Ord here seems to suggest that Weak NU is biased toward giving too much weight to suffering. But Weak NU would reject this claim, and would hold that it is appropriate to give more weight to suffering (e.g. because suffering of intensity x is worse for someone’s wellbeing than happiness of intensity x is good).

A non sequitur regarding wellbeing

It might be rare to have a case where everyone is made worse off at once, but there are greatly many lesser cases. For example, in some cases it [i.e. Weak NU] will say that it is immoral to watch the end of the film while you are really hungry, even if this tradeoff increases your wellbeing, because the suffering counts more morally. Other things being equal, you are obligated to prevent your friends and family improving [sic] their wellbeing through their judicious tradeoffs too. I find this to be an absurd consequence.

Again, Weak NU need not imply that one should prevent others from improving their wellbeing, as Weak NU may hold that suffering has greater weight in terms of what contributes to individual wellbeing (cf. Mathison, 2018). And again, one could also argue that CU would (in theory) oblige us to prevent people from “improving their wellbeing through their own judicious tradeoffs”, such as when people refuse to endure intense suffering in order to gain a “sufficient” amount of happiness.

“This would be a crazy view”

Note that Absolute or Lexical NU could avoid this if they said that happiness didn’t contribute to wellbeing at all, or that it only broke ties, but this would be a crazy view about what is good for someone.

Ord again resorts to saying that two of the views he aims to criticize are “crazy” (although similar views have been defended in Schopenhauer, 1819; 1851; Wolf, 1996; 1997; 2004; Fehige, 1998; Breyer, 2015). This is not much of an argument against the views in question, let alone a good-faith one.

Moreover, proponents of Absolute or Lexical NU need not hold that happiness makes no contribution to wellbeing “at all” (or that it only breaks ties). Proponents of Absolute and Lexical NU may hold that happiness contributes to wellbeing indirectly, by reducing suffering and other bad states.

Reiterating a fallacious objection

Lexical Threshold NU could avoid this in cases below its threshold if it said that happiness and suffering were equally important below that level, but this would create a particularly odd kind of discontinuity and wouldn’t seem to satisfy their intuitions either.

Once again, we should be clear that abrupt thresholds are not a necessary feature of views that entail lexicality between mild and intense suffering. And even if one did accept a sharp threshold in the kind of view Ord describes, this threshold would arguably not need to be “particularly odd”. For instance, one could hold that mild discomfort can always be outweighed by pleasure, but that genuine pain is always lexically worse than any amount of mild discomfort or lost pleasure (cf. Klocksiem, 2016).

Implausible claims about practical implications

Implausible practical implications

Many advocates of NU claim that on average human lives have net negative intrinsic moral value. This must be true of Absolute NU, Lexical NU, and Strong Practically-Negative Utilitarianism.

As noted earlier, someone who endorses “Strong Practically-Negative Utilitarianism”, in the sense that they think it is almost always most effective to focus on the alleviation of suffering, would not necessarily have to think that “on average human lives have net negative intrinsic value”. Such a person might think that we can generally help others more effectively by working to reduce suffering among non-human animals, and they may think that the reduction of suffering is generally more tractable than is the promotion of happiness (cf. Vinding, 2020, 1.3).

Moreover, it is not even strictly true that one would have to think that “on average human lives have net negative intrinsic moral value” if one endorses “Strong Practically-Negative Utilitarianism” based on Ord’s narrow definition — i.e. “Classical Utilitarianism with the empirical belief that suffering outweighs happiness in all or most human lives”. After all, one could think that most human lives are “net negative” yet that the arithmetic mean of all people’s wellbeing is still positive.

It is also the kind of thing that advocates of Lexical Threshold NU and Weak NU tend to say. However, this has some really implausible implications.

For example, it implies that other things being equal it would be good if people get murdered or if one’s mother were to die. Things are not always equal, and you may perhaps think that in many cases the bad secondary effects are enough to outweigh the benefits of the people dying. I find this difficult to believe since according to NU, one’s mother’s death is astoundingly good: roughly as good as eliminating all of her suffering and having her live out the rest of her live [sic] in constant bliss. It seems unlikely to me that the pain of family members’ grief would outweigh this great ‘benefit’ (particularly if you remember that your mother would otherwise experience such grief too, and that she would otherwise die at a later date inflicting almost the same amount of grief on loved ones).

It seems that one could make similar arguments against CU. For example, according to CU, there are many people whose future lives will have “net negative” intrinsic value, and hence CU would imply that “other things being equal it would be good if these people get murdered”. And one could further argue that such murders would often be good in practice. Yet I suspect that most classical utilitarians would reply that other things are generally not equal, and that it would usually be very bad if such people were to be murdered. I think NUs can make a similar reply with at least as much force (see also Vinding, 2020, 8.2).

Second, Ord’s use of the term “astoundingly good” seems misleading. As Simon Knutsson notes, NU would not imply that an earlier end to life would be “good” in the sense of adding positive value. Hedonistic NU — i.e. NU focused purely on the reduction of suffering — would merely deem it less bad than the alternative, when considered in isolation. And the caveat “in isolation” is indeed critical, since these analyses of individual lives are quite far removed from the practical context in which we find ourselves, where the positive roles of a life will often far outweigh its painful contents.

Third, there are various forms of NU that do not imply that a shorter life would be better, even when considered in isolation. For instance, preference-based NU would consider it intrinsically bad if a person’s preference against death were to be thwarted (even if the death involved no experienced suffering), and other forms of NU may likewise consider death a harm because it involves disrupted life projects, which certain views of wellbeing would consider intrinsically bad (cf. Knutsson, 2016).

Fourth, one could argue that CU has implications that are far worse than does (hedonistic) NU in these regards. For example, if we go with the example of “one’s mother’s death” provided by Ord, then CU would imply that it would be “astoundingly good” if one’s mother died and got replaced by isolated matrix lives of pure bliss. Indeed, CU would consider it “astoundingly good” even if one’s mother got tortured for an arbitrarily long duration before she died if this in turn created a “sufficient” amount of happiness occurring in isolated matrix lives. (And note that the term “astoundingly good” is more apt here than in the case of NU, since the classical utilitarian indeed would say that we can generate a net sum of positive value in this case.)

Implausible claims about murder

However, even if secondary effects always conspire to restore a semblance of normality, a Negative Utilitarian would still have to believe that it is great for the person when they get murdered and would be great overall if only people didn’t react so badly to it. This is a large bullet to bite.

I believe Ord is wrong in claiming that NUs would “have to believe that it is great for the person when they get murdered”. After all, a person who gets murdered might well experience horror and suffering that is much greater than the suffering they would otherwise experience, which may be especially likely given a lexical view that assigns overriding disvalue to the most extreme suffering. (And again, Ord’s use of the word “great” is arguably misleading, since a more accurate description would be something like “less bad than the alternative”.)

I also think Ord is wrong when he claims that, according to NU, it would “be great overall if only people didn’t react so badly” to murder. I fail to see why this would follow. Indeed, one could argue that we should generally “react more badly” and do far more to prevent murders — especially sadistic murders — from the perspective of NU (cf. Vinding, 2022, 13.3.3).

Implausible claims about healthcare

Similarly, it [i.e. NU] also implies that much healthcare and lifesaving is of enormous negative value. It says that the best healthcare system is typically the one that saves as few lives as possible, eliminating all the suffering at once. This turns healthcare policy debates on their heads and means we shouldn’t be emulating France or Germany, but should instead look to copy failed states such as North Korea.

Ord’s claim that NU generally recommends copying the healthcare policies of “failed states such as North Korea” seems unfounded. I would argue that the policies of countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands are more likely to be worth emulating by the lights of NU, seeing that these countries allow access to a wide range of pain relieving drugs, and since they have legalized voluntary euthanasia (cf. Vinding, 2022, 13.3.4).

Extending the list of practical claims based on implausible premises

This list could easily be extended, either focusing on the fact that many forms of NU would prefer almost everyone dead, or on the fact that they would resist people making happiness/suffering tradeoffs which are in those people’s interests.

Again, in terms of practical implications, there are strong reasons to disbelieve that hedonistic NU “would prefer almost everyone dead”, and indeed to believe that hedonistic NU would recommend actively preventing deaths in cases where individuals prefer to continue living (Vinding, 2020, 8.2). And this is even more true of versions of NU that consider disrupted life projects and thwarted preferences against death to be intrinsically bad.

As for the claim that NU would “resist happiness/suffering tradeoffs that are in people’s interests”, we can again note that many apparent happiness/suffering tradeoffs are plausibly about preventing greater suffering, and hence that NU would disagree with people’s self-regarding choices less often than one might think. And a proponent of NU could further argue that it only disagrees with people’s choices in the “right” cases — i.e. when people make overall suffering-increasing choices. (Of course, if we factor in other-regarding considerations as well, it is true that people often make greatly suboptimal decisions, but this is also true by the standards of CU; people’s actions generally fall far short of the best they could do by any impartial standard.)

Additionally, we can again note that CU would in theory oblige people to endure intense suffering in order to attain “sufficient” amounts of intense happiness, even if the people in question would prefer not to have those experiences. One can thus argue that CU goes against people’s own stated preferences in worse ways than does NU (because unlike NU, it would impose extreme suffering on people for the sake of giving them pleasure, cf. Vinding, 2020, ch. 3).

Other views that fit NU intuitions better?

Alternatives

I hope by now I’ve shown that there are a number of serious looking problems [sic] for NU. If you were a supporter of some form of NU, then perhaps you are trying to work out some way to hold onto your view, or to invent a new variant that manages to avoid some of the most serious arguments. Before you do, I’d like to invite you to consider some of the reasons that you might have initially become interested in NU and see if there aren’t other views that would fit those intuitions just as well but without such dire consequences.

I still do not think Ord has demonstrated that NU has particularly “dire consequences”, let alone that it has worse implications than do other views on offer. I thus see little reason why a supporter of NU should feel compelled to “try to work out some way” to hold onto their view, or to “invent a new variant” of NU in light of Ord’s attempted critique.

Are prioritarian intuitions an underlying driver of NU intuitions?

Typical examples that motivate NU can be be [sic] captured by other views. For example, in the earlier quotation, Popper said:

‘human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway’

Popper’s example involves removing suffering from someone rather than adding happiness to someone who is already happy. It thus involves two contrasts. One is between improving the lot of a worse-off person or a better-off person, and one is between improving a life through the addition of happiness or the removing of suffering. There is a well known moral intuition that we should prioritise helping the worse off and this is much more widely accepted than NU. Perhaps this is what is lying behind people’s intuitions that they should help the suffering person over the happy one.

While this prioritarian intuition does seem more widely endorsed than NU, it is not clear whether it is more widely endorsed than is a moral asymmetry between suffering and happiness (the aspect of NU that Ord set out to criticize). Indeed, one could argue that this moral asymmetry is often what lies behind the prioritarian intuition rather than vice versa (cf. Vinding, 2020, 8.7).

To test this, consider a case where the you [sic] could avoid minor suffering in the life of someone who has been extremely fortunate and is very happy, or you could bestow some happiness to someone whose life is truly wretched. If you would prefer to grant the happiness in this case, or if you even feel much more uncertain about it, then that is an indication that you were at least partly motivated by concerns for the worst off rather than the primacy of relieving suffering. Such an intuition can be accounted for in the theories of Prioritarianism, Egalitarianism, and Sufficientarianism. I think that these theories are themselves flawed (which goes beyond the scope of this essay), but I find them much more plausible than NU.