A wide variety of views can support a focus on preventing worst-case outcomes. More than that, it appears that the views of population ethics held by the general population also, on average, imply a priority on preventing futures with large numbers of miserable beings. My aim in this post is to elaborate on this point and to briefly explore its relevance.

Asymmetric scope sensitivity

A recent study set out to investigate people’s intuitions on population ethics, exploring how people judge the value of different populations of happy and unhappy individuals (Caviola et al., 2022a). The study included a number of sub-studies, which generally found that people endorse a weak asymmetry in population ethics. That is, people tend to believe that miserable lives and suffering weigh somewhat stronger than do happy lives and happiness, even when the misery and happiness in question are claimed to be equally intense (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 8).

One of the sub-studies sought to examine the participants’ evaluations of populations of varying sizes (these participants were all from the US). Subjects were asked to consider different pairs of hypothetical civilizations, each of which would last for millions of years and differ only in terms of their size. Specifically, the participants were asked to rate how strongly they would prefer a larger over a smaller happy population, as well as how strongly they would prefer a smaller over a larger unhappy population. These ratings were made in pairwise population comparisons of 1,000 vs 10,000, 1 million vs. 10 million, and 1 billion vs 10 billion people (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 11).

The study found that subjects generally preferred a larger happy population in the case of 1,000 vs 10,000 people, yet this preference declined as the populations in question became larger. In fact, the preference for larger happy populations declined so strongly that the participants on average preferred the smaller happy population in the 1 billion vs 10 billion comparison (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 12). The study likewise reported that “the median response for the ideal population size was 1.5 million for the happy civilization” (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 12).

In contrast, subjects generally preferred a smaller unhappy population, and this preference became increasingly strong when population pairs became larger. As the authors summarized these findings: “people show ‘asymmetric scope sensitivity’ with respect to happy and unhappy population sizes. And this asymmetric scope sensitivity was more pronounced the larger the population sizes got.” (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 12).

It is worth noting that the study did not specify whether the populations under consideration would represent all humans in the world, though it was specified that each of the populations in the pairwise comparisons would have “multiple Earth-like planets available to them” (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 11). Subjects were also informed that the populations in question would have “no issues with resource depletion, environmental degradation or overpopulation”, yet it is nevertheless possible that worries about overpopulation influenced the responses of some of the participants (Caviola et al., 2022a, p. 11, p. 13).

Why this popular view would support a focus on preventing worst-case outcomes

It is fairly straightforward to see how people’s average preferences regarding different populations of happy and unhappy people would support a focus on preventing worst-case outcomes.

If people’s average preference for a larger happy population declines and eventually reverses, whereas the average preference for smaller unhappy populations gets stronger as the populations in question increase, then it seems to follow that people on average consider it more valuable to prevent the existence of a very large unhappy population than to ensure the existence of a very large happy population. In other words, people generally seem to think that it is more valuable to prevent worst-case outcomes than to create best-case outcomes. And this asymmetry may well become stronger when the prospect of space colonization and astronomical stakes enter the picture. That is, when the populations under consideration are not just 1 billion versus 10 billion, but many orders of magnitude larger — e.g. 1 trillion vs 10 trillion, 1 quadrillion vs 10 quadrillion, etc.

To be sure, the findings above do not directly show that people endorse a strong asymmetric scope sensitivity for astronomical-scale populations, since it does not include any such populations. (It would be great to have studies that directly explore this issue.) Yet given the trend toward increasingly strong preferences for smaller populations in comparisons of larger populations, it seems reasonable to expect that the asymmetry would also hold — and plausibly grow even stronger — on astronomical scales.

But again, even if people’s average preference for smaller unhappy populations does not get stronger still for populations larger than 10 billion, it is worth reiterating that people already seem to consider it more valuable to prevent worst-case outcomes when considering Earth-scale populations.

Other surveys likewise indicate that the prevention of future suffering, including worst-case outcomes in particular, is considered a key priority among the general population. For example, one survey (n=14,866) asked people what a future civilization should strive for, and found that the most popular aim, ranked highest by roughly a third of the respondents, was “minimizing suffering” (Future of Life Institute, 2017). Similarly, a small survey (n=99) asked people whether they would accept one minute of extreme suffering in order to add a given number of happy years to their lives, and found that a plurality, around 45 percent, said that no number of happy years could lead them to accept the offer (Tomasik, 2015).

Lastly, a pilot study (n=172) conducted by Caviola et al. asked people at what ratio of happy to unhappy lives they would be willing to push a button to create a new world, and found that people on average thought that it required roughly a ratio of 100:1 happy people to unhappy people (Caviola et al., 2022b, p. 7; Contestabile, 2022, sec. 4). 1 In other words, people generally seem to endorse a rather strong asymmetry when it comes to the creation of new worlds, which may suggest that people would likewise endorse a strong asymmetry in the case of space colonization aimed at populating new worlds. (But again, it would be helpful to have studies that probe this question directly.)

Similar views in the academic literature

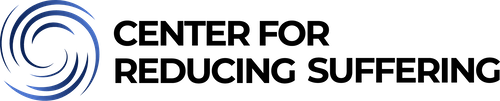

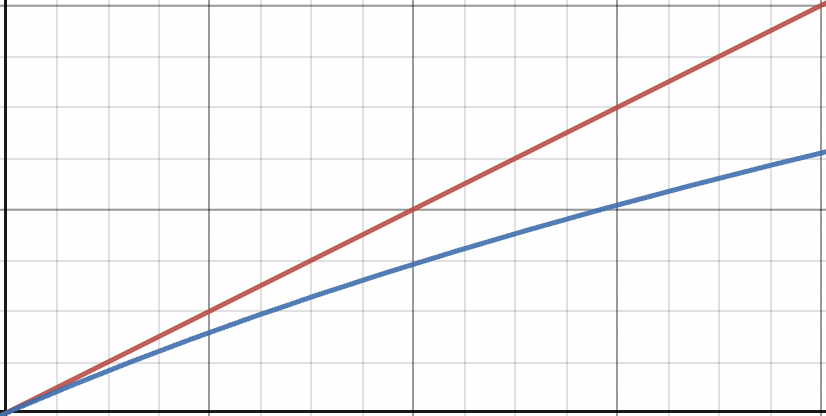

It is worth noting that people’s average preferences regarding population sizes appear to resemble a class of views that have been explored, and to some degree endorsed, by academic philosophers. In particular, asymmetric scope sensitivity is implied by theoretical views that maintain that happy lives, or states of happiness in general, add diminishing marginal value to the world, whereas miserable lives, or states of suffering in general, add non-diminishing disvalue to the world (Hurka, 1983; 2010; Parfit, 1984, pp. 406-412; Knutsson, 2016).2

These asymmetric views likewise tend to support a focus on the prevention of worst-case outcomes, especially on astronomical scales, where the asymmetry can become extremely strong (Vinding, 2020, sec. 6.2). The figures below illustrate how a view of this kind might see the population-ethical asymmetry on different scales, being fairly weak on smaller scales while being strong on larger scales.

Why this is relevant: Potential implications for democratic institutions

What is the relevance of people’s average preferences regarding population ethics, and why, specifically, is it relevant what those views would imply for our priorities?

To my mind, the main relevance of these findings lies in their potential implications for the policies of representative political institutions. That is, if political efforts to improve the long-term future are to represent people’s views and preferences in a genuinely democratic fashion, then these findings seem to carry significant implications for those political efforts and priorities.

In short, if the findings regarding asymmetric scope sensitivity do indeed reflect people’s average preferences on population ethics, they seem to imply that representative political institutions would make it a priority to prevent worst-case outcomes that involve large miserable populations. At the very least, the findings suggest that the prevention of such outcomes would be a stronger priority for democratic institutions than would the creation of a very large happy future population.

Notice that the statements above are descriptive in nature, being phrased in terms of what democratic political institutions would do, if they were to be representative. I am not claiming that the priorities in question would be right by virtue of being democratic. But given that many of us happen to live in (more or less) representative democracies, it seems worth investigating which priorities those systems would imply by the standards of their own stated ideals.

To elaborate further, the popular support for asymmetric scope sensitivity suggests that a focus on preventing worst-case outcomes is by no means a fringe priority, but rather a priority that most people seem to weigh considerably higher than the creation of a very large happy population. Those aiming to prevent worst-case outcomes may thus have good reason to advance this goal in the political realm, with an awareness that the aim of preventing worst-case outcomes plausibly has greater democratic legitimacy and support than does the goal of creating a very large happy population (cf. the studies and surveys cited above). And this seems especially true if efforts to create a large happy population come at the opportunity cost of preventing worst-case outcomes, or even if they come at the opportunity cost of failing to prevent intense suffering for currently existing individuals.

Acknowledgments

For helpful comments, I am grateful to David Althaus and Tobias Baumann.

References

Caviola, L. et al., (2022a). Population ethical intuitions. Cognition, 218, 104941. Ungated

Caviola, L. et al. (2022b). Supplementary Materials for Population ethical intuitions. Ungated

Contestabile, B. (2022). Is There a Prevalence of Suffering? Ungated

Future of Life Institute. (2017). Superintelligence survey. Ungated

Hurka, T. (1983). Value and Population Size. Ethics, 93(3), pp. 496-507.

Hurka, T. (2010). Asymmetries In Value. Nous, 44(2), pp. 199-223. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2016). What is the difference between weak negative and non-negative ethical views? Ungated

Parfit, D. (1984). Reasons and Persons. Oxford University Press.

Tomasik, B. (2015). A Small Mechanical Turk Survey on Ethics and Animal Welfare. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2020). Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications. Ratio Ethica. Ungated

- The absolute population sizes that were included in the questions in this study were rather small, ranging from 10 to 1,000, and hence people’s asymmetric scope sensitivity likely did not apply strongly in these versions of the ratio question. One might thus expect that the ratio would be even higher if the question were phrased in terms of larger populations; this also seems worth exploring in future studies.[↩]

- Specifically, Hurka argues that happy lives plausibly add diminishing marginal value to the world (Hurka, 1983), whereas he appears sympathetic to an asymmetric evaluation of the disvalue of suffering that would regard its marginal disvalue as non-diminishing, or at least as less strongly diminishing (cf. Hurka, 2010, p. 200). Similarly, Parfit explicitly wrote that “the badness of extra suffering never declines” (p. 406), while he appeared to consider it more plausible that pleasure has diminishing marginal value, even though he ultimately felt compelled to reject the latter view based on its implications (Parfit, 1984, pp. 406-412).[↩]