by Teo Ajantaival. First published in 2021. Revised in 2024. Chapter 3 in the book “Minimalist Axiologies: Alternatives to ‘Good Minus Bad’ Views of Value“.

Readable as a standalone post.

| Previous: | Next: |

| Varieties of minimalist moral views: Against absurd acts | Minimalist extended very repugnant conclusions are the least repugnant |

Summary

Minimalist views of value (axiologies) are evaluative views that define betterness solely in terms of the absence or reduction of independent bads, such as suffering. This chapter looks at minimalist axiologies that are impartial and welfarist (i.e. concerned with the welfare of all sentient beings), with a focus on their theoretical and practical implications. For example, these views reject the ‘Very Repugnant Conclusion’ implied by many offsetting (‘good minus bad’) views in population ethics.

Minimalist views are arguably neglected in population ethics due to their apparent implication that no life could be axiologically positive. After all, minimalist views reject the concept of independent goods. Yet these views are perfectly compatible with the notion of relational goods, and can thereby endorse relationally positive lives that make a positive difference for other beings.

This notion of relationally positive value is entirely excluded by the standard, restrictive assumption of treating lives as isolated value-containers. However, this assumption of ‘all else being equal’ is practically always false, enabling the possibility of highly positive lives according to minimalist views.

Minimalist views become more intuitive when we adopt a relational view of the overall value of individual lives, that is, when we don’t track only the causally isolated “contents” of these lives, but also their (often far more significant) causal roles.

What is axiology?

Axiology is the philosophical study of value.1 Here, I will focus on questions related to independent value, relational value, and resolving conflicts between values.

Independent versus relational value

Axiology is centrally concerned with the question of what things, if any, have independent value, also known as intrinsic value.

‘Axiologies’ in the plural refer to specific views on this axiological question. Once we assume a specific axiology — that is, a view that ascribes independent value to certain entities or states — we may then understand the value of all other things as extrinsic, instrumental, or relational in terms of their effects on these entities or states.

This distinction between independent and relational value applies at the level of our axiological theory. The distinction can blur at the level of our everyday perception, and this blurring is often practically adaptive.

For instance, we may both formally deny that something has independent value, yet also correctly perceive that it does have value, without constantly unpacking what this value relationally depends on. Our decision-making tends to be more efficient when we perceive the various objects of our goals as simply having value, even when these goals are only indirectly related to what we ultimately value.

Thus, we may do well in practice by treating many widely-held values — such as autonomy, health, or friendship — as independently valuable things to safeguard and promote, at least until they run into conflicts with each other. When they conflict, we have reason to clarify what the underlying or ultimate source of their value might be.2

Resolving conflicts between values

To figure out what things have independent value, we commonly devise thought experiments where only a single thing is meant to be changing, all else being equal. We then ask our supposedly value-tracking intuitions whether it seems true that this isolated change is accompanied by a change in value.

Based on such thought experiments of isolated value, one might come to endorse at least two, independent standards of value: “The more positive pleasure (or bliss), the better”, and “The less agony, the better”.

At first glance, these two standards of value may seem to be perfectly compatible with each other, given that the more blissful a mind-moment is, the less agonized it is. Yet dilemmas arise if we want to simultaneously follow both standards more widely, as they are not always perfectly anticorrelated. That is, we often cannot both “maximize bliss” and “minimize agony” at the same time, because even as these two guiding principles may seem to be polar opposites, they do not always constitute a coherent twin-principle like “Head North, Avoid South”.

The field of population ethics has highlighted ways in which these principles come apart, pulling our intuitions into mutually incompatible directions. And it has highlighted the lack of consensus about how to compare the intrinsic value of positive pleasure against the intrinsic disvalue of agony.3

To resolve conflicts between the seemingly intrinsic dual values of positive pleasure versus agony, one option is to establish acceptable tradeoff ratios (or “priority weights”) between them, so as to clarify how much a change in one weighs against a change in another.Another approach is to reject the assumption that there are any truly independent goods to begin with. This is the approach of minimalist axiologies, where the value of purported goods like bliss is weighed in terms of how well they reduce bads like agony. (Note that according to some views, such as views in the Epicurean tradition, bliss is understood as the complete absence of any pain or unpleasantness, and hence “maximizing bliss” and “minimizing unpleasantness” are indeed equivalent twin-principles on this conception of bliss.4)

What are minimalist axiologies?

The less this, the better

Minimalist axiologies essentially say: “The less this, the better”. In other words, their fundamental standard of value is about the avoidance of something, and not about the maximization of something else.

To list a few examples, minimalist axiologies may be formulated in terms of avoiding…

- cravings (tranquilism5; certain Buddhist axiologies6);

- disturbances (Epicurean minimalism4);

- pain or suffering (Schopenhauer7; Richard Ryder8);

- frustrated preferences (antifrustrationism9); or

- unmet needs (Häyry10; some interpretations of care ethics11).

This chapter looks at minimalist axiologies that are impartial12 and welfarist13: focused on the welfare of all sentient beings.14

Relational value in light of impartial avoidance goals

In tradeoffs between multiple, seemingly independent values, minimalist axiologies avoid the issue of having to establish independent priority weights for different goods and bads so as to resolve their mutual conflict. (By contrast, offsetting axiologies face this issue in tradeoffs such as creating bliss for many at the cost of agony for others.)

Instead of using different standards of value for goods and bads, minimalist axiologies construe ‘positive value’ in a purely relational way, with regard to an overall avoidance goal for all beings. This transforms the apparent conflict between goods and bads into an empirical question about the degree to which the goods can reduce the bads, and thus still be genuinely valuable in that way.

When we look at only one kind of change in isolation, it may seem intuitive that bliss is independently good and agony independently bad. Yet we may also feel internally conflicted about tradeoffs where value and disvalue need to be compared with each other, so that we could say whether some tradeoff between them is “net positive” or not. Put differently, we may have both promotion intuitions and avoidance intuitions that seem to lack a common language.

To solve these dilemmas, minimalist axiologies would respect promotion intuitions to the degree that they are conducive to the overall avoidance goal, yet reject the creation of more (isolated) value for some at the cost of disvalue for others.15

For example, suffering-focused minimalism would respect the promotion of wellbeing in the place of suffering, but not of wellbeing at the cost of suffering, all else equal.16

Thus, minimalist axiologies sidestep the problem of having to find acceptable “tradeoff ratios” between independent goods versus bads, replacing it with the relational question of how the objects of our promotion intuitions could help with the overall avoidance goal.

Contents versus roles

Minimalist axiologies may appear to imply that “No life could be positive or worth living”. And such a conclusion might seem implausible to our intuitions, which might say that “Surely lives can be positive or worth living”.

Yet minimalist axiologies merely imply that individual lives cannot have positive value when understood as “isolated value-containers”, which they never are in the real world.17 And given that the “no life could be worth living” conclusion only follows when we adopt this highly unrealistic isolated view of individual lives, our intuitive objection to this conclusion need not stem from the sentiment that “Surely lives can have at least some isolated positive value”. Instead, we might reject the conclusion because we reject, or fail to accurately imagine, its unrealistic premise of treating lives as isolated value-containers.

According to minimalist views, positive value is not something that we “have”, “contain”, or “accumulate” in isolation, but rather something that we “do” for a wider benefit. This relational view of positive value may conflict with the Western cultural tendency18 to see individuals as “independent, self-contained, autonomous entities”19 and to ascribe positive value to the collection of particular experiences for their own sake. Thus, minimalist views may be neglected by the heavily Western-influenced field of population ethics, where we often draw unrealistically tight boxes around individual lives in our quest to isolate that which makes a life valuable or worth living.

To better explore our intuitions about supposedly isolated positive value without the confounding influence of our positive roles-tracking intuitions, it may be helpful to explicitly imagine that we are offered the chance to create a causally isolated black box whose existence has no effects beyond itself. How positive could the box be? Minimalist views say that it cannot be positive at all, regardless of what it contains.

With all that said, the next section will consider the implications of minimalist versus offsetting views when we do play by the rules of population ethics and draw boxes around the contents of individual lives. Overall, many counterintuitive conclusions in population ethics may be attributed to the view of positive value as an independent and independently aggregable phenomenon, or a “plus-point” that can be summed up or stacked in isolation from the positive roles of the individual lives or experiences that contain it.

How do minimalist views help us make sense of population ethics?

Population ethics is “the philosophical study of the ethical problems arising when our actions affect who is born and how many people are born in the future”.20 A subfield of population ethics is population axiology, which is about figuring out what makes one state of affairs better than another. Some have argued that this is a tricky question to answer without running into counterintuitive conclusions, at least if we make the assumption of independently positive lives.21 Minimalist axiologies do not make this assumption, and hence they avoid the conclusions that are pictured in the three diagrams in the next three subsections.22

Before looking at the diagrams, let us already note a way in which people might implicitly disagree about how to interpret them. Namely, some of the diagrams contain a horizontal line that indicates a “zero level” of “neutral welfare”, which may be interpreted in different ways. For example, when diagrams illustrating the (Very) Repugnant Conclusion contain lives that are “barely worth living”, some may think that these lives involve “slightly more happiness than suffering”, while others may think, as Derek Parfit originally did, that they “never suffer”.23

A different interpretation of the horizontal line is used in antifrustrationism by Christoph Fehige, where welfare is defined as the avoidance of preference dissatisfaction (or ‘frustration’). When Fehige’s own diagrams contain the horizontal line, it just means the point above which the person has “a weak preference for leading her life rather than no life”.24 On Fehige’s view, the lives with “very high welfare” are much better off than the lives “barely worth living” that still contain a lot of frustration.

Yet if we assume that the lives above the horizontal line have all their preferences satisfied, “never suffer”, and have no bads in their lives whatsoever, then minimalist axiologies would find no problem in the Mere-Addition Paradox or the Repugnant Conclusion. Even so, they would still not strictly prefer larger populations, finding all populations of such problem-free lives rather equally perfect (in causal isolation).However, it seems unusual to imagine that the lives “barely worth living” would be subjectively completely untroubled or “never suffer”. Thus, we will here assume that the lives just above the line are not completely untroubled, as seems common in population ethics.25

The Mere-Addition Paradox

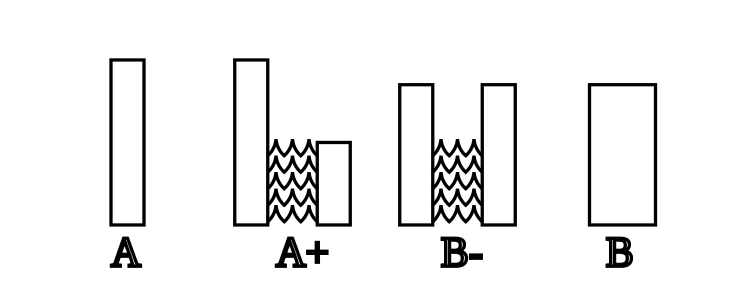

Derek Parfit’s Mere-Addition Paradox (Figure 3.1) is based on a comparison of four populations. Each bar represents a distinct group of beings. The bar’s width indicates their numbers, and the height their level of welfare. We assume that every being in this diagram has “a life worth living”. (The populations in A+ and B− consist of two isolated groups; the population in B is simply the two groups of B− combined into one.)

Figure 3.1. The Mere-Addition Paradox.26

The paradox results from the following evaluations that together contradict some people’s intuitive preference for the high-average population of A over the lower-average population of B:

- Intuitively, “A+ is no worse than A,” since A+ simply contains more lives, all worth living.

- Next, “B− is better than A+,” since B− has both greater total welfare and greater average welfare.

- Finally, “B− is equal to B,” since B is simply the same groups, only combined.

- Now, “B is better than A,” based on steps 1–3.

This paradox is a problem for those who strongly feel that “A is better than B”, yet who are also sympathetic to total utilitarianism. One reason to avoid average utilitarianism or averagism is that it implies “sadistic conclusions”, in which average welfare is increased by the addition of hellish lives.27 Yet if we assume that the lives in B contain more subjective problems than do the lives in A, then minimalist axiologies would prefer A over B without averagism.

Essentially, Fehige’s solution is to assume that the welfare of a life depends entirely on its level of preference dissatisfaction or ‘frustration’. On this view, a population of satisfied beings cannot, other things being equal, be improved by the “mere addition” of new, less satisfied beings. This is because the frustration of those new beings is an additional subjective problem, as compared to the non-problematic non-existence of their imaginary counterparts in the smaller population.28

While this may be a theoretically tidy solution to the Mere-Addition Paradox, critics have objected that it depends on a theory of welfare that they find to be counterintuitive, incomplete, or unconvincing.

However, we would be wise to abstain from hastily dismissing minimalist views as being counterintuitive, because there are plenty of ways to interpret them in more intuitive ways without losing their theoretical benefits. A lot of their perceived incompleteness might result from the thought experiments themselves, which imply that we are not actually supposed to imagine the kind of lives that are familiar to us, but only the hypothetically isolated kind of lives that have absolutely no positive roles beyond themselves.

The Repugnant Conclusion

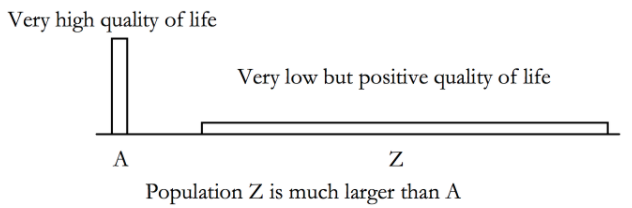

By continuing the logic of “mere addition”, we arrive at the ‘Repugnant Conclusion’ (Figure 3.2):

In Derek Parfit’s original formulation[,] the Repugnant Conclusion is characterized as follows: “For any possible population of at least ten billion people, all with a very high quality of life, there must be some much larger imaginable population whose existence, if other things are equal, would be better even though its members have lives that are barely worth living” (Parfit 1984). … The Repugnant Conclusion is a problem for all moral theories which hold that welfare at least matters when all other things are equal.29

Figure 3.2. The Repugnant Conclusion.30

Minimalist axiologies avoid the Repugnant Conclusion, as they deny that the lives “barely worth living” would constitute a vast heap of independent “plus-points” in the first place. For example, Fehige would assume that the lives with “a very high quality of life” would be quite free from problems, which is better, all else equal, than a much larger set of lives that still have a lot of their preferences unsatisfied.

As noted by another commenter on Fehige’s paper:

Among its virtues, [antifrustrationism] rescues total utilitarianism from the repugnant conclusion. If utility is measured by the principle of harm avoidance instead of aggregated preference satisfaction, utilitarianism does not, as the accusation often goes, entail that it is better the more (acceptably) happy lives there are[, other things being equal].31

Fehige’s theory of welfare is seemingly dismissed by some philosophers on the grounds that it would, counterintuitively, deny the possibility of lives worth living:

However, a theory about welfare that denies the possibility of lives worth living is quite counter-intuitive [Ryberg, 1996]. It implies, for example, that a life of one year with complete preference satisfaction has the same welfare as a completely fulfilled life of a hundred years, and has higher welfare than a life of a hundred years with all preferences but one satisfied. Moreover, the last life is not worth living (Arrhenius 2000b).32

Yet this objection seems to imply that a life could be worth living only for its own sake, namely for some kind of satisfaction that it independently “contains”, and to deny that a life could be worth living for its positive roles. Again, we need to properly account for the fact that Fehige’s model is only comparing lives in causal isolation.

As soon as we step outside of the hypothetical, isolated case where “other things are equal” and start comparing these lives in our actual, interpersonal world, we may well see how, even on minimalist terms, the subjectively perfect one-year life could be much less valuable (overall, for all beings) than would be the subjectively near-perfect century. After all, many of our preferences and preferred actions have significant implications for the welfare of others.

However, it is not necessarily counterintuitive to prefer the perfect year, or even non-existence, over the imperfect century in the hypothetical case of complete causal isolation, where we can make no positive difference in any way. Regardless of how we felt during the year, or during the century, others would live as if we never had. Thus, we may question the overall worth of extending our life solely for our own sake in the experience machine, or in an equally solipsistic preference satisfaction machine, provided that it solves no problem beyond ourselves.

The Very Repugnant Conclusion

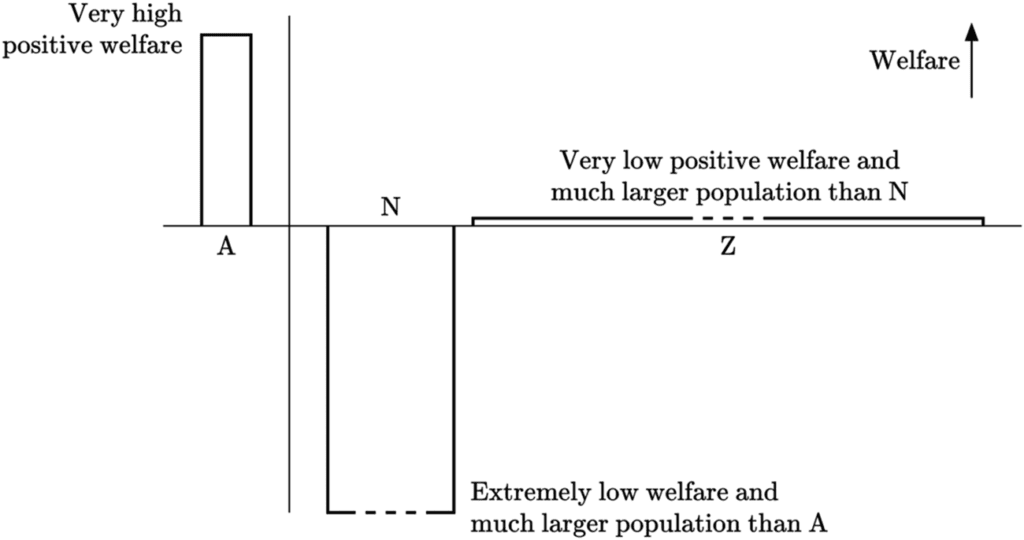

The Repugnant Conclusion was termed repugnant due to the intuition that a legion of lives “barely worth living” cannot be better than a smaller population of lives that each have a very high welfare. Some say that in this case, the intuition is wrong and that we should “bite the bullet” and follow the utilitarian math of additive aggregationism.33 However, presumably fewer people would accept the ‘Very Repugnant Conclusion’ (VRC), in which the better world, according to many offsetting views, contains a lot of subjectively hellish lives, supposedly “compensated for” by a vast number of lives that are barely worth living (Figure 3.3):

There seems to be more trouble ahead for total [offsetting] utilitarians. Once they assign some positive value, however small, to the creation of each person who has a weak preference for leading her life rather than no life, then how can they stop short of saying that some large number of such lives can compensate for the creation of lots of dreadful lives, lives in pain and torture that nobody would want to live?34

Figure 3.3. The Very Repugnant Conclusion.35

In other words:

Let W1 be a world filled with very happy people leading meaningful lives [A]. Then, according to total [offsetting] utilitarianism, there is a world W2 which is better than W1, where there is a population of [purely] suffering people [N] much larger than the total population of W1, and everyone else has lives barely worth living [Z] – but the population is very huge.36

One way to avoid the VRC is to follow Fehige’s suggestion and interpret utility as “a measure of avoided preference frustration”. On this view, utilitarianism “asks us to minimize the amount of preference frustration”, which leads us to prefer W1 over W2.37 As noted by Fehige, “Maximizers of preference satisfaction should instead call themselves minimizers of preference frustration.”38

Every minimalist axiology would prefer W1 over W2 due to being structurally similar to Fehige’s view — that is, none of them would say that the supposed “plus-points” of W2 could somehow independently “counterbalance” the agony of the others, regardless of the number of the lives “barely worth living”.

In contrast, the VRC is a problem for many offsetting axiologies besides purely hedonistic ones:

Consider an axiology that maintains that any magnitude of suffering can be morally outweighed by a sufficiently great magnitude of preference satisfaction, virtue, novelty, beauty, knowledge, honor, justice, purity, etc., or some combination thereof. It is not apparent that substituting any of these values for happiness in the VRC makes it any more palatable[.]39

Minimalist views also avoid what are arguably even stronger objections against offsetting total views, such as the theoretical choices of ‘Creating hell to please the blissful’ (Figure 4.5) and ‘Intense bliss with hellish cessation’ (Figure 5.2). More on the comparative implications between minimalist and offsetting views in the next chapters.

Solving problems: A way to make sense of population ethics?

In general, a way to avoid the VRC (and the two other conclusions above) is to hold that ethics is about solving and preventing problems, and not about creating new, unneeded goods elsewhere for their own sake. On this view, any choice between two populations (all else equal) is based on considering which population contains the overall greater amount of problematic states, such as extreme suffering.

This problem-focused view rejects the metaphor that ethical problems could be “counterbalanced” instead of prevented:

[Only] the existence of such problematic states imply genuine victims, while failures to create supposed positive goods (whose absence leaves nobody troubled) do not imply any real victims — such “failures” are mere victimless “crimes”. … According to this view, we cannot meaningfully “cancel out” or “undo” a problematic state found somewhere by creating some other state elsewhere.40

Generally, the metaphor of ethical counterbalancing may stem from our common tendency to think in terms of polar opposites. When we speak of a ‘negative’ state, we may naturally assume that it could be counterbalanced by a ‘positive’ state of equal magnitude.41 Yet the mere observation of a negative state does not imply the possibility of a corresponding positive or ‘anti-negative’ state.42 The opposite of a problematic state may, instead, be just an unproblematic state, with no equivalent ‘anti-problematic’ state to counterbalance it.43

What are we comparing when we make the assumption of “all else being equal”?

Isolated value-containers

The ceteris paribus assumption is often translated into English as something like “all else equal”, “all else unchanged”, or “other things held constant”.44 That is, we exclude any changes other than those explicitly mentioned. When we make this assumption in population ethics, the idea is to compare any two hypothetical populations only with respect to their explicit differences, such as the level and distribution of welfare among those populations, with no other factors influencing our judgment.

Yet we need to be mindful of the potential pitfalls when we compare populations in this way. For instance, it is much easier said than done to completely rule out the influence of all factors other than those explicitly mentioned. We may think we have done it upon reading the words “all else equal”, yet we may in fact need to spend some time and imaginative effort to actually prevent such supposedly external factors from influencing our judgment.

This pitfall is exacerbated by the fact that the “all else equal” assumption is often left highly implicit, with little attention paid to how radically it changes what we are talking about. Quite often, we only see it as a parenthetical (as if ignorable) remark, with no instruction for how to best account for it. Or we may not see it at all, as in situations where it is an unvoiced background assumption, in which we are trusted to have the contextual awareness to take it properly into account even with no explicit reminder to do so.

How we account for the ceteris paribus assumption can influence the distance that we see between theory and practice, which in turn can influence our potentially action-guiding views, such as our views on what kinds of lives can be positive or worth living (and what for).

To illustrate, let us imagine a scenario where the ceteris paribus assumption would actually be true: namely, we are comparing only “isolated value-containers” or “isolated Matrix-lives” that never interact with each other in any way.45 If this sounds radical, then we may not always realize how radical the assumption in fact is. After all, we may intuitively assume that “positive lives” would also play positive social roles and make a difference beyond themselves. Yet these factors are supposed to be ruled out when we are comparing lives ceteris paribus, solely for their own sake.In effect, when we apply the ceteris paribus assumption to the value of individual lives, we are restricted to a kind of “isolated view” of lives worth living, as if that which makes a life worth living would necessarily have to be something that it contains, rather than its roles and relations beyond itself.

Counterintuitive boundaries

Our practical intuitions about the overall value of lives — such as of all the lives “barely worth living” in the (Very) Repugnant Conclusion — may implicitly be tracking not only the “contents” of these lives (i.e. their own level of welfare), but also their overall effects on the welfare of others.

And in practice, it may indeed seem like a repugnantly bad idea to trade away a high-welfare population for a legion of lives “barely worth living”, as the latter might seem to not have enough wellbeing as a resource to adequately take care of each other in the long term. (A practical intuition in the opposite direction is also possible, namely that a larger population could create more goods, insights, and resources that everyone could benefit from, and thus have a brighter future in the long run.)

Yet to give any weight to such instrumental effects, even implicitly, would already conflate our evaluation of those hypothetical lives solely for their own sake. After all, we are supposed to compare only the level and distribution of welfare as shown in the population ethics diagrams, and to ignore our practical intuitions about how the lives or populations might evolve or unfold in different ways if interpreted as the starting point of a story in the real world.

Our practical intuitions are adapted for an interpersonal world with a time dimension: two features of life that are difficult for us to put aside when entering thought experiments about the value of other beings. Thus, we may need to explicitly remind ourselves that the population ethics diagrams are, in effect, already depicting the complete outcome, with no relevant interactions or time-evolutions left outside the box.

What do these views imply in practice?

Naive versus sophisticated minimalism

Even if minimalist views avoid many of the conclusions that have been called tricky problems for other views in population ethics, one might still worry that minimalist views could have absurd implications in practice. Yet regardless of what specific implications one has in mind, it is worth noting that many of them might stem not only from the “isolated view” that ignores the positive roles of individual lives, but also from the hasty logic of a “naive” form of consequentialism, which further ignores the positive roles of various widely established social norms, such as those of respecting autonomy, cooperation, and nonviolence.46

A naive consequentialism is not based on a nuanced view of expected value thinking,47 and can instead fall victim to a kind of “narrative misconception” of consequentialism, in which the view would support “any means necessary” to bring about its axiologically ideal “end state”.

One could argue that the idea of a ‘utilitronium shockwave’ (i.e. turning all accessible matter into pure bliss) amounts to such a misconception about the practical implications of classical utilitarianism.48 In the case of minimalist axiologies, this misconception looks like the claim that we must, at any cost, “seek a future where problems are eventually reduced to zero”, which is very different from minimizing the amount of problems over all time in expectation.

After all, only the second kind of thinking — namely, expected value thinking without any fixed destination — is sensitive to risks of making things worse. By contrast, the first, misconceived view is more like fixating on a particular story of what we must eventually achieve at some particular time in the future.

And instead of being sensitive to risks of making things worse, the story might include a point, as many stories do, at which the protagonists must engage in an “all in” gamble to ensure that they bring about an ideal world “in the end”. In other words, the narrative misconception of consequentialism might hold that “what justifies the means” is the endpoint, or the possibility of reaching it, rather than the overall minimization of problems with no fixed destination.

More concretely, a naive version of minimalism might lead us to ignore the positive norms of everyday morality as soon as there would (apparently) be even the slightest chance of bringing about its hypothetically ideal “end state”, such as an empty world, even if doing so would violate the preferences of others or risk multiplying the amount of problems in the future by many orders of magnitude.

By contrast, a nuanced or “sophisticated” version of minimalism would be concerned with the “total outcome” — which spans all of time — and be highly sensitive to the risk of making things worse overall. For instance, any aggressively violent strategy for “preventing problems” would very likely backfire in various ways, such as by undermining one’s credibility as a potential ally for large-scale cooperation, ruining the reputation of one’s (supposedly altruistic) cause, and eroding the positive norm of respecting individual autonomy.49

Given that the backfire risks depend on complex interactions that happen over considerable spans of time, we are likely to pay them insufficient attention if our thinking of real-world interventions is as simplistic as the boxes that collapse hypothetical populations into two-dimensional images. Of course, a nuanced, practical minimalism would not be like thinking in terms of boxes, and would instead take the relational factors and empirical uncertainties into account.50

Compatibility with everyday intuitions

What, then, do these views imply in practice, assuming a sophisticated minimalism over all time? The second half of Magnus Vinding’s Suffering-Focused Ethics is an accessible and extensive treatment of basically the same question, particularly for views that prioritize minimizing extreme suffering.51 That is, the practical implications of minimalist views are probably in large part the same as those of many suffering-focused views.

Yet minimalist views differ from at least some suffering-focused views in one respect, which is that minimalist views work completely without the concept of independent positive value, placing full emphasis on relational positive value.

For that reason, minimalist views may appear as if they were somehow uniquely opposed to many things that we might intuitively cherish as being intrinsically valuable — as if none of our intuitively positive pursuits would have any positive worth or weight to justify their inevitable costs.

Yet minimalist views need not imply anything radical about the quantity of positive value that we intuitively attribute to many things at the level of our everyday perception.

After all, the kinds of things that we may deem “intrinsically valuable” at an intuitive level are often precisely the kinds of things that rarely need any extrinsic justification in everyday life, such as sound physical and mental health, close relationships, and intellectual curiosity.

If required, we often could “unpack” the value of these things in terms of their indirect, long-term effects, namely their usefulness for preventing more problems than they cause. But when our intuitively positive pursuits have many beneficial effects across a variety of contexts, we are often practically wise to avoid spending the unnecessary effort to separately “unpack” their value in relational terms.

Additionally, the more we unpack and reflect on the relational benefits of our intuitively positive pursuits, the more we may realize the full magnitude of their positive value, even according to minimalist views. After all, if our perception and attribution of positive value is focused on our positive feelings in the immediate moment, we may actually underestimate the overall usefulness of things such as maintaining good health and relationships, learning new skills, and coming up with new insights. Namely, it is of course desirable when such things help us feel better, yet perhaps the bulk of their value is not how they affect our own feelings in the moment, but what roles they play for all beings.

In other words, while minimalist views may not assign positive value to any particular experiences solely for their own sake, they can still value all the physical, emotional, intellectual, and social work, as well as any other activities, that best enable us collectively to alleviate problems for all beings.Overall, if the goal is to minimize problems, we are faced with the dauntingly complex meta-problem of identifying interventions that can reasonably be expected to prevent more problems than they cause. And this meta-problem will require us to combine a vast amount of knowledge and supportive values. That is, minimalist views do not imply that we hyper-specialize in this meta-problem in a way that would dismiss all seemingly intrinsic values as superfluous. Rather, they imply that we adhere to a diverse range of these values so as to advance a mature and comprehensive approach to alleviating problems.52

Preventing instead of counterbalancing hell

Of course, it would be a ‘suspicious convergence’53 if all the things that we may perceive as being intrinsically valuable would also be relationally aligned with the impartial minimization of problems. Yet the everyday implications of minimalist views need not be very different from those of other consequentialist views, as all of them imply a personal ideal of living an effective life in alignment with some overall optimization goal — which, in turn, may recommend a broadly shared set of habits and heuristics for everyday living.

Where the views differ the most may be in their large-scale implications. For instance, instead of primarily ensuring that we expand out into space, minimalist views would imply that we prioritize steering the future away from worst-case scenarios. After all, many scenarios of space colonization may, depending on their guiding values, vastly increase the amount of suffering over all time (in expectation).54

Self-contained versus relational flourishing

When psychologists speak of flourishing, it can have many meanings. As a value-laden concept, it is often bundled together with things like “optimal growth and functioning”, “social contribution”, or “having a purpose in life”.55

Before we load the concept of flourishing with independent positive value, as is seemingly done by the authors of works such as Utilitarianism.net56, The Precipice57, and What We Owe the Future58, it is worth carefully considering whether this value is best seen as independent or relational in the axiological sense.

Minimalist views would not see positive flourishing as any kind of “self-contained” phenomenon of isolated value for one’s own sake. Yet minimalist views are perfectly compatible with a relational notion of positive flourishing as personal alignment with something beyond ourselves. For instance, minimalist flourishing could mean that we are skillfully serving the unmet needs of all sentient beings, aligning our wellbeing with the overall prevention of illbeing.

In practice, a minimalist understanding of “optimal growth and functioning” would probably entail a combination of strategic self-investment and healthful living (similar to other impartial welfarist views). After all, we first need to patiently grow our strengths, skills, and relationships before we can sustainably and effectively apply ourselves to help others. And because life can be long, it makes sense to keep growing these capacities, meeting our needs in harmony with the needs of others, and to seek and find the best ways for us to play positive roles for all sentient beings.59

Without the concept of intrinsic positive value, how can life be worth living? A more complete view

In standard, theoretical population ethics, what we see are only the isolated “welfare bars” of what all the individual lives independently “contain”. Yet in practice, we also have hidden “relational roles bars” of what our lives “do” beyond ourselves.

On any impartial and welfarist view, our own “aggregate welfare” is often a much smaller part of our life’s overall value than is what we do for the welfare of others. Thus, when we think of our own ideal life (or perhaps the life of our favorite historical or public figure), we are often practically right to focus on this life’s roles for others, and not only, or even mostly, on how it feels from the inside.

In particular, since the value of the life’s roles is ultimately measured in the same unit of value as its own welfare, we can directly say that the roles can be much bigger than what any single life independently “contains”.60

In the case of minimalist views, we may find that a sufficient reason to endure hardship is to prevent hardship, reduce inner conflict, and lighten the load for all sentient beings over all time.

And if we further zoom into the nature of “effort”, we may find that basically all of our daily struggles are much easier to bear compared to instances of the most intense pains.61 Thus, we may already find some lightness and relief in being relatively problem-free at the personal level. And we may further realize that we can play highly worthwhile roles by focusing our spare efforts on helping to relieve such extreme burdens in the big picture.

By contrast, if we assume that our burdens are worthwhile for the sake of some intrinsic positive value, then we again face theoretical tradeoffs like the VRC, as well as the practical question of whether we would allow astronomical amounts of extreme suffering to take place for the sake of creating astronomical amounts of purported positive goods.

Finally, we might question the practical relevance of thinking that a life could be worth living only for some kind of “self-contained” satisfaction. After all, our practical intuitions and dilemmas never concern tradeoffs between fully self-contained lives, which none of us ever are.

Even without the concept of intrinsic positive value, a life can be worth living for its positive roles.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Magnus Vinding for help with editing, and to Aaron Gertler for commenting on an early draft.

I am also grateful for helpful comments by Tobias Baumann, Simon Knutsson, and Winston Oswald-Drummond.

Commenting does not imply endorsement of any of my claims.

References

Anonymous. (2015). Negative Utilitarianism FAQ. utilitarianism.com/nu/nufaq.html

Armstrong, S. (2019). The Very Repugnant Conclusion. lesswrong.com/posts/6vYDsoxwGQraeCJs6

Arrhenius, G. (2000a). An impossibility theorem for welfarist axiologies. Economics & Philosophy, 16(2), 247–266. doi.org/10.1017/S0266267100000249

Arrhenius, G. (2003). The Very Repugnant Conclusion. In K. Segerberg & R. Sliwinski (Eds.), Logic, Law, Morality: Thirteen Essays in Practical Philosophy in Honour of Lennart Åqvist (pp. 167–180). Uppsala University. philpapers.org/rec/ARRTVR

Arrhenius, G., Ryberg, J., & Tännsjö, T. (2014). The repugnant conclusion. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2014 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/repugnant-conclusion

Breyer, D. (2015). The cessation of suffering and Buddhist axiology. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 22, 533–560. blogs.dickinson.edu/buddhistethics/files/2015/12/Breyer-Axiology-final.pdf

Chappell, R. Y., Meissner, D., & MacAskill, W. (2021). Population Ethics: The Total View. utilitarianism.net/population-ethics#the-total-view

DiGiovanni, A. (2021a). A longtermist critique of “The expected value of extinction risk reduction is positive”. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/RkPK8rWigSAybgGPe

Fehige, C. (1998). A Pareto Principle for Possible People. In C. Fehige & U. Wessels (Eds.), Preferences (pp. 508–543). Walter de Gruyter. fehige.info/pdf/A_Pareto_Principle_for_Possible_People.pdf

Fox, J. I. (2022). Does Schopenhauer accept any positive pleasures? European Journal of Philosophy. doi.org/10.1111/ejop.12830

Gloor, L. (2017). Tranquilism. longtermrisk.org/tranquilism

Gómez-Emilsson, A. (2019). Logarithmic Scales of Pleasure and Pain. qri.org/blog/log-scales

Gómez-Emilsson, A. & Percy, C. (2023). The heavy-tailed valence hypothesis: The human capacity for vast variation in pleasure/pain and how to test it. Frontiers in Psychology, 14:1127221. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1127221

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010b). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83. doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Häyry, M. (2024). Exit Duty Generator. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 33(2), 217–231. doi.org/10.1017/S096318012300004X

Jollimore, T. (2023). Impartiality. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2023 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2023/entries/impartiality

Karlsen, D. S. (2013). Is God Our Benefactor? An Argument from Suffering. Journal of Philosophy of Life, 3, 145–167. philosophyoflife.org/jpl201309.pdf

Knutsson, S. (2019). Epicurean Ideas about Pleasure, Pain, Good and Bad. simonknutsson.com/epicurean-ideas-about-pleasure-pain-good-and-bad

Knutsson, S. (2021b). The world destruction argument. Inquiry, 64(10), 1004–1023. doi.org/10.1080/0020174X.2019.1658631

Knutsson, S. (2022b). Undisturbedness as the hedonic ceiling. simonknutsson.com/undisturbedness-as-the-hedonic-ceiling

Knutsson, S. (2024). Answers in population ethics were published long ago. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/answers-in-population-ethics-were-published-long-ago

Leighton, J. (2024, March 20). Jonathan Leighton at EAGxAustralia 2023 – Unexpected Value: Prioritising the Urgency of Suffering [Video]. youtube.com/watch?v=4M5fgkWWujg

Lewis, G. (2016). Beware surprising and suspicious convergence. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/omoZDu8ScNbot6kXS

MacAskill, W. (2022). What We Owe the Future. Basic Books. goodreads.com/book/show/59802037

Markus, H. R. & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

Ord, T. (2020). The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity. Hachette Books. goodreads.com/book/show/48570420

Parfit, D. (1984/1987). Reasons and Persons. Clarendon Press. goodreads.com/book/show/327051

Remmelt. (2021). Some blindspots in rationality and effective altruism. forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/LJwGdex4nn76iA8xy

Ryder, R. (2001). Painism: A Modern Morality. Open Gate Press. goodreads.com/book/show/1283431

Schopenhauer, A. (1819/2012). The World as Will and Idea (Vol. 3 of 3). Project Gutenberg. gutenberg.org/files/40868/40868-pdf.pdf

Schopenhauer, A. (1851/2004). The Essays of Arthur Schopenhauer: Studies in Pessimism. Project Gutenberg. gutenberg.org/files/10732/10732-h/10732-h.htm

Schroeder, M. (2018). Value theory. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition). Stanford University. plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/value-theory

Sherman, T. (2017). Epicureanism: An Ancient Guide to Modern Wellbeing (MPhil dissertation). University of Exeter. ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/32103/ShermanT.pdf

Todd, B. (2021). Expected value: how can we make a difference when we’re uncertain what’s true? 80000hours.org/articles/expected-value

Tomasik, B. (2013d). Omelas and Space Colonization. reducing-suffering.org/omelas-and-space-colonization

Tännsjö, T. (2020). Why Derek Parfit had reasons to accept the Repugnant Conclusion. Utilitas, 32(4), 387–397. doi.org/10.1017/S0953820820000102

Vinding, M. (2020c). On purported positive goods “outweighing” suffering. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/on-purported-positive-goods-outweighing-suffering

Vinding, M. (2020d). Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications. Ratio Ethica. magnusvinding.files.wordpress.com/2020/05/suffering-focused-ethics.pdf

Vinding, M. (2020e). Why altruists should be cooperative. centerforreducingsuffering.org/research/why-altruists-should-be-cooperative

Vinding, M. (2022e). A phenomenological argument against a positive counterpart to suffering. centerforreducingsuffering.org/phenomenological-argument

Vinding, M. (forthcoming). Compassionate Purpose: Personal Inspiration for a Better World. magnusvinding.com/books/#compassionate-purpose

Wolf, C. (1997). Person-Affecting Utilitarianism and Population Policy. In J. Heller & N. Fotion (Eds.), Contingent Future Persons. Kluwer Academic Publishers. web.archive.org/web/20190410204154/https://jwcwolf.public.iastate.edu/Papers/jupe.htm

| Previous: | Next: |

| Varieties of minimalist moral views: Against absurd acts | Minimalist extended very repugnant conclusions are the least repugnant |

Notes

- Schroeder, 2018.[↩]

- Cf. the topic of value commensurability as discussed in 1.1.2 and in Schroeder, 2018. (More on everyday perception and practical heuristics in 2.3.2.2; 3.5.2; 6.2.)[↩]

- Many of the relevant thought experiments in population ethics will be visualized shortly in 3.3 and Chapter 4.[↩]

- 1.3.1.2; cf. Sherman, 2017; Knutsson, 2019, 2022b.[↩][↩]

- 1.3.1.4; Gloor, 2017.[↩]

- Anonymous, 2015, sec. 2.2; Breyer, 2015.[↩]

- Schopenhauer, 1819, “the negative nature of all satisfaction”; 1851, “negative in its character”; Fox, 2022, “pleasures of distraction”.[↩]

- Ryder, 2001, p. 27.[↩]

- 1.3.2.1; Fehige, 1998. See en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antifrustrationism.[↩]

- Häyry, 2024.[↩]

- Cf. iep.utm.edu/care-ethics. Specifically, a minimalist interpretation of care ethics could say that our main responsibility is to ensure that there are fewer unmet needs, and not to create additional needs at the cost of neglecting existing or expected needs.[↩]

- On moral impartiality, see Jollimore, 2023.[↩]

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Welfarism.[↩]

- Thus, the chapter is not meant to cover axiologies that might be technically minimalist, yet which are partial or focused on non-welfarist avoidance goals (like minimizing human intervention in nature, or avoiding the loss of unique information).[↩]

- More on the assumption of causally isolated value in 3.4.[↩]

- Cf. Vinding, 2020d, chap. 3.[↩]

- More in 3.4.[↩]

- Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010b, “Independent and interdependent self-concepts”.[↩]

- Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Remmelt, 2021, “We view individuals as independent”.[↩]

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Population_ethics.[↩]

- Cf. Arrhenius, 2000a. For a counterpoint to the common narrative that population ethics is particularly difficult, see Knutsson, 2024.[↩]

- The conclusions are named “paradoxical” or “repugnant” after the intuitions of people who find them troubling. Generally, people differ a lot in which intuitions they are willing to “give up” in population ethics.[↩]

- As noted by Anthony DiGiovanni (2021a) on Parfit’s original formulation of the Repugnant Conclusion (RC):

[Parfit] explicitly says the beings in this world “never suffer.” Many suffering-focused axiologies would accept the RC under this formulation—see e.g. Wolf (1997)—which is arguably a plausible conclusion rather than a “repugnant” bullet to bite. However, in many common formulations of the RC, the distinguishing feature of these beings is that their lives are just barely worth living according to axiologies other than strongly suffering-focused ones, hence they may contain a lot of suffering as long as they also contain slightly more happiness.[↩]

- Fehige, 1998, p. 534.[↩]

- See, for instance, Knutsson, 2024, sec. 4.4.[↩]

- From en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mere_addition_paradox.[↩]

- Cf. Parfit, 1984, p. 422, “Hell Three”; Arrhenius, 2000a, p. 251, “The Sadistic Conclusion”.[↩]

- Fehige, 1998. Fehige’s use of the term ‘preference frustration’ is much broader than the everyday feeling that we call frustration. After all, basically all lives in the real world have at least some of their preferences frustrated, even if some may be free from the feelings of frustration.[↩]

- Arrhenius, Ryberg, & Tännsjö, 2014.[↩]

- From Arrhenius, Ryberg, & Tännsjö, 2014.[↩]

- Karlsen, 2013, p. 160.[↩]

- Quote from Arrhenius, Ryberg, & Tännsjö, 2014, sec. 2.4.[↩]

- Additive aggregation entails that the total value of a group or state of affairs is simply the sum of the individual value of each of its members.[↩]

- Fehige, 1998, pp. 534–535.[↩]

- From Tännsjö, 2020.[↩]

- From Armstrong, 2019. Formal discussions of the VRC are sometimes traced back to Arrhenius, 2003. However, the VRC was discussed already in Fehige, 1998.[↩]

- Fehige, 1998, pp. 535–536.[↩]

- Fehige, 1998, p. 518.[↩]

- DiGiovanni, 2021a, sec. 1.1.1.[↩]

- Vinding, 2020c, sec. 2.4.[↩]

- Vinding, 2020d, pp. 155–156; Knutsson, 2021b, sec. 3; Leighton, 2024.[↩]

- Vinding, 2022e.[↩]

- Cf. Figure A1.1.[↩]

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ceteris_paribus.[↩]

- Not even by acausal “influence”.[↩]

- More in Chapter 2 and in 6.3.[↩]

- Cf. Todd, 2021; probablygood.org/core-concepts/expected-value.[↩]

- For the utilitronium shockwave thought experiment by David Pearce, see hedweb.com/social-media/pre2014.html.[↩]

- Cf. 6.3.1; Vinding, 2020e.[↩]

- More on the “narrative misconception” of consequentialism in 5.3.[↩]

- Vinding, 2020d, pp. 141–277.[↩]

- For more on what minimalist views might support in practice, see 2.3.2.2; 5.3; and Chapter 6.[↩]

- Cf. Lewis, 2016.[↩]

- Tomasik, 2013d.[↩]

- en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flourishing.[↩]

- Chappell, Meissner, & MacAskill, 2021, “flourish”.[↩]

- Ord, 2020, “flourish”.[↩]

- MacAskill, 2022, “flourish”.[↩]

- More in 6.4.1. For a book-length exploration of compassionate impact as a positive purpose in life, see Vinding, forthcoming.[↩]

- More in 6.2.[↩]

- Cf. Gómez-Emilsson, 2019; Gómez-Emilsson & Percy, 2023.[↩]