By Simon Knutsson and Magnus Vinding

August 22, 2024

This text is a general introduction to suffering-focused ethics. We describe different types of suffering-focused ethical views and explain some of the reasons why we find suffering-focused views reasonable. We also bring up and discuss some common misunderstandings and objections, and briefly cover some practical implications.

1. The core of suffering-focused ethical views

In essence, suffering-focused ethical views give a foremost priority to the reduction of suffering.1 According to such views, there is something especially important or urgent about alleviating and preventing suffering. Usually, the primary concern is severe suffering rather than discomforts.

A simple example of a clearly suffering-focused view is the view that our only moral obligation is to reduce suffering as much as we can. Yet there are many types of suffering-focused views, as we will see in the next section. For instance, there can be differences in how strongly suffering is prioritised, as well as differences in terms of which considerations besides suffering are taken into account.

Which views count as being suffering-focused? There is no sharp line that delineates exactly when a view is suffering-focused or not; it is a matter of degree. Still, it is useful to observe that there is a diverse group of ethical views according to which the reduction of suffering has a foremost priority.2

2. Different types of suffering-focused views

Suffering-focused views can come in all the shapes and sizes that moral views come in. Some say that all that matters is the consequences of our actions. Others talk about character and virtues such as compassion, or about separate moral principles that need to be balanced against one another (for example, one principle about reducing suffering and another principle about respecting individual autonomy). Still others are less theoretical and leave more to moral judgement given the particulars of a situation.3

There are many examples of suffering-focused views in both historical and contemporary ethical traditions. We are most familiar with Western sources and talk mostly about those, but there are also Eastern traditions that are suffering-focused. For instance, some of the main strands of Buddhist ethics give special priority to the reduction of suffering.4 This includes the Mahayana tradition of Buddhism, in which 8th-century philosopher Shantideva argued that we should “dispel the pains of all”.5

Below, we describe some examples of suffering-focused ethical views. We try to convey the diversity that exists and we focus on views that can be found in the literature (as opposed to merely possible views).

2.1 Consequentialist views

When a suffering-focused view is impartial and only concerned with minimising suffering or ill-being, it is a form of (strong) negative utilitarianism.6 The most popular version of that view is probably the view that one should minimise the total amount of suffering, or especially minimise the amount of extreme suffering.7 Negative utilitarian views, like the one just mentioned, are members of the large family of consequentialist views, but there are other suffering-focused consequentialist views besides negative utilitarianism. For example, a view according to which one should reduce other bad things besides suffering, such as injustice, would be another variant of (strong) negative consequentialism.

There are also suffering-focused consequentialist views that give a moral role to positive well-being or positive final value (the positive value something has for its own sake). According to these views, consequences for positive well-being or positive value matter morally, but reducing suffering is generally most important. We call such views ‘weak negative’ forms of utilitarianism or consequentialism, although others might prefer different labels such as ‘negative-leaning’, ‘partially asymmetric’, or ‘partially suffering-focused’.8

2.2 Views focused on consequences along with other considerations

Some authors have similar views but include other considerations besides consequences. For example, there are moral views that put a duty to minimise suffering front and centre, while also including other moral duties and rights that, among other things, protect the life and autonomy of individuals.9 Similarly, there are suffering-focused views that give great importance to consequences as well as to personal qualities such as being considerate, incorruptible, and patient.10

2.3 Views based on categorical norms

There are traditions in ethics in which authors use different approaches and vocabularies from those we have mentioned so far. In these other traditions, people seem to think about morality differently and use other building blocks when they formulate their ethical views. For example, some authors propose categorical norms or prohibitions. A suffering-focused example is Ohlsson (1979). According to him, it is unacceptable to purchase positive consequences for those with acceptable lives if it happens at the expense of someone else’s death or unbearable suffering or degradation.11 In Ohlsson’s ethical system, this Principle of Unacceptable Tradeoffs is a categorically binding norm, which is always to be given precedence.12

2.4 Prioritising the reduction of suffering in certain domains, such as politics

Some views give a special or even overriding priority to the reduction of suffering in certain domains, while being more permissive of different priorities in other domains. For instance, some views hold that the reduction of suffering should generally be the primary aim in politics and public policy, while allowing more room for other aims in people’s private conduct.13

2.5 Ideas that tend toward a focus on suffering

The views we have mentioned so far are explicitly about the moral importance of suffering. But one can also arrive at a suffering-focused moral view more indirectly, such as through complementary ideas about population ethics, well-being, and value. For example, if someone holds that it does not make things better to increase the number of beings, then that doesn’t directly imply an ethical focus on reducing suffering. It is possible to hold that the highest moral priority is to preserve certain paintings. Still, one can see how this idea about the value of creating new beings, when combined with other ethical ideas that people generally find reasonable, would tend to result in a focus on reducing suffering. The same applies to the idea that well-being consists in the absence of certain bads, such as experiential disturbances or frustrated preferences.14

3. Why we find suffering-focused views reasonable

To understand a given view and its appeal, it may be helpful to understand why proponents of that view find it sensible. In that spirit, we will here outline some of the reasons why we find suffering-focused views to be reasonable. To be clear, we will not here seek to defend suffering-focused views, since that would require more space and going into more detail than what we find suitable in this introductory text. Instead, we will just present some of the main reasons why we find suffering-focused views compelling, while referring readers to other sources for more information and arguments.

3.1 The importance of severe suffering

Our main concern is severe suffering. An example of what we have in mind is the suffering of someone whose entire family has just been murdered. This is not among the most gruesome scenarios that happen or that one can imagine. As another example, one can think about the most horrendous torture methods and deaths throughout history and in the world today, as well as what the future might bring in terms of similar or even worse atrocities. Why would the prevention or alleviation of such severe suffering be so important?

One reason is simply that the victim feels horrible. Although it might be impossible to grasp exactly what the victim experiences, we can still have a rough idea that it feels awful and much worse than any ordinary unpleasantness that we are familiar with.15

Second, the victim’s judgement, involuntariness, and lack of consent matter morally.16 We can broadly distinguish two kinds of situations involving severe suffering:

(a) The victim actively disapproves. For example, the victim judges that their suffering cannot be counterbalanced by purported goods, they find their situation unbearable, or they reject the notion that they consent. In such situations, we find it morally appropriate to respect the victim’s judgement.17

(b) The victim does not approve. There is, for instance, no consent, voluntariness, or judgement that their suffering is worth it. The victim might be unable to judge or consent because they belong to a species that cannot formulate those kinds of thoughts or attitudes, or because they are in such distress that they cannot think in those terms. In this kind of situation, it is a serious moral problem that there is severe suffering that is not accepted by the victim.18

As a final point, we mention some other aspects that can accompany the devastating situations we have in mind. These aspects are plausibly worth preventing for their own sake and add to the moral gravity of the victim’s fate: someone having their life destroyed, losing what they cherish the most, being brutally violated, getting their dreams and projects crushed, and not being compensated in any way.

3.2 The importance of severe suffering compared to purported goods

Why is severe suffering so important compared to other things, particularly compared to the creation of purported goods? What we have already said about the moral importance of severe suffering helps inform our answer to that question. In addition to those points, we can explore this comparative question more directly, by looking at comparisons between the moral importance of severe suffering and the creation of purported goods.19

As a general matter, we find it reasonable to conclude that the alleviation and prevention of extreme suffering is morally important in a way that the creation of purported goods is not. The relief and prevention of extreme suffering has a unique moral urgency and importance, whereas the creation of purported goods seems to have no similar moral urgency or importance, if indeed it has any at all.

To say more about the urgency aspect: Consider ongoing cases of severe suffering due to starvation or violent oppression. Alleviating such suffering is urgent, of course (even if we only alleviate that suffering without increasing positive welfare).20 Consider then the opportunity to enable someone with a problem-free life to experience more intense pleasure (in a way that does not also reduce suffering) and the opportunity to create more beings with purportedly positive welfare (who would not also reduce suffering for others).21 It seems to us that it is not urgent to increase the pleasure and positive welfare, and especially not as urgent as alleviating the misery. After all, to not increase pleasure and positive welfare seems wholly fine and unproblematic, whereas any failure to prevent extreme suffering is just the opposite: it is an excruciatingly felt moral problem.

In addition to this consideration of cases, we note that there are common notions such as emergencies and someone being in desperate need of help that are generally not about increasing pleasure or other purported goods. Rather, these seem to be about reducing suffering and other bads. This makes sense to us. If we reflect on what should be labelled an ‘emergency’ and the like, we find that it concerns the alleviation and prevention of severe suffering and other major harms — not increasing positive value.22

Furthermore, causing or failing to prevent severe suffering is generally a grave moral failure (it can even amount to the worst, extreme immorality), whereas this does not seem to be the case for failing to create purported goods (that nobody needs and whose absence causes no problem). Some speak of moral monsters and evil actions and persons, but these are seemingly about matters such as serious harms, suffering, and malice, and hardly about failing to create positive value.23

The existence of a victim is also morally relevant. Generally speaking, causing or failing to prevent severe suffering implies a harmed and morally wronged victim. By contrast, the failure to create purported goods does not involve any victims, and no one is harmed or wronged, in our view.24 This is one reason why a failure to create purported goods does not seem to be a moral failure of a comparable kind (and not a moral failure of any kind).25

Moreover, if we look at different kinds of outcomes, it seems reasonable to us that adding severe suffering to a given outcome would make that outcome overall bad and morally worth preventing, even if it contains vast amounts of purported goods.26 For example, consider a state of unbearable suffering that a tormented victim does not consent to, and which the victim judges to be impossible to outweigh by purported goods. That would give that victim a plausible claim to the outcome being unacceptable and worth preventing. The victim could legitimately raise a complaint and reject any alleged desirability of the outcome.27 Conversely, we fail to see how or why adding purported goods to an outcome that contains such unbearable suffering could ever make the outcome overall good, acceptable, or morally worth creating. In particular, we fail to see how purported goods are supposed to be able to counterbalance or make up for such extreme suffering. That notion seems quite mysterious and unmotivated to us.28

All in all, even if we grant that there is such a thing as positive final value, we find that it is always more important to prevent severe suffering than to create positive final value.29

3.3 The non-existence of positive final value

We find it plausible that nothing has positive value for its own sake. In other words, there is no positive final value.30 This idea is controversial and it is not a necessary ingredient in a suffering-focused view. Moreover, it is not a standard reason for holding a suffering-focused view, and our views do not hinge on it.31 Still, we mention it because it can lead to a suffering-focused view, we find it reasonable, and it probably needs some explanation.

More precisely, this section is about the non-existence of all of the following: positive final value, positive well-being, and experiences that are a positive counterpart to suffering. We will briefly try to convey how this makes sense to us.

Let us start with the issue of final value and picture empty space. We disagree with the view that something is missing, that there is a waste and an unrealised potential, and that it would be better in itself if things were added. In contrast, we see empty space as unproblematic, flawless, and peaceful. Morally speaking, there is no need to change anything. You cannot make it better by adding things, and there is no moral imperative to do so.

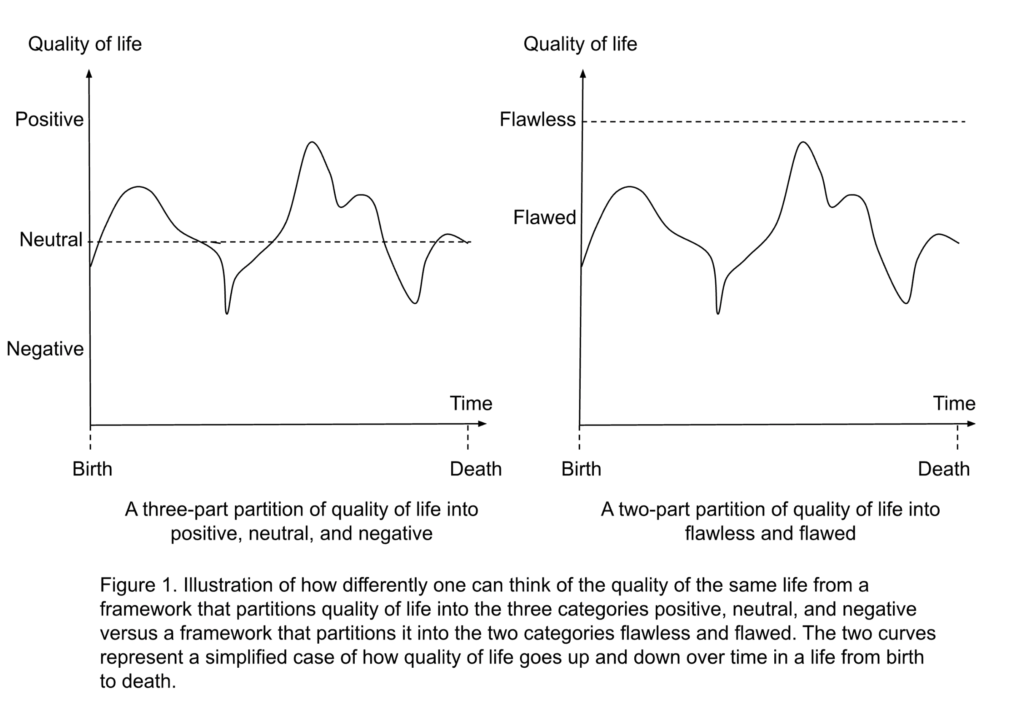

We can also use this framework of flawless versus flawed when thinking about quality of life, happiness, and experiences.32 For example, we reject the idea that there is a neutral quality of life above which quality of life is positive. Instead, we would say that lives can be flawless or flawed, and one cannot do better than complete flawlessness. Flawlessness is not good or positive in itself; it simply occurs when there are no flaws of any kind.33

We illustrate these two different ways of thinking about quality of life in Figure 1 below.34 The figure shows two different perspectives on the same individual life. Both perspectives agree that life can get better and worse, and both grant the existence of peak periods in life. The difference between the two perspectives is that the first divides quality of life into three categories: positive, negative, and neutral. In contrast, the second perspective (our view) divides quality of life into two categories: flawless and flawed. In the figure, the individual never reaches the flawless level, which makes sense because in real life, we might rarely or never reach a perfect or completely flawless quality of life (e.g. a state with absolutely no experiential disturbances or frustrated preferences).35

It is worth clarifying how the non-existence of positive final value and the like is compatible with some common ways of speaking. In our view, it can still be useful in daily life to informally speak in terms such as “this feels great”, “that’s good”, and “I’m very well”. Such statements can be considered shorthands for more complicated statements, such as “I’m much better off than many other people” or “I’m much better off than I could have been or used to be”. Our point is not to oppose such informal ways of speaking in daily life, but rather to explain the position that when making moral decisions, there is actually no positive final value or positive quality of life that one could increase, so efforts to improve things should instead be about reducing problems.

Another clarification is that our view does not entail that experiential states of excitement, amusement, gladness, and so on do not exist. Of course, such states do exist, and we also have such experiences.36 Our view is rather that no such experiences (nor any other experiences) are a positive counterpart to suffering, none of them can bring us above a flawless quality of life, and none of them have positive final value.37

4. Misunderstandings about suffering-focused ethics

4.1 World destruction

The perhaps most common allegation against some suffering-focused views is that they support destroying the world or killing everyone. The allegation can be an argument that one can direct against certain suffering-focused views (as well as non-suffering-focused views), and we will talk about that in Section 5.38 Here we merely note that the allegation sometimes involves basic misunderstandings.

We focus on the misunderstanding of directing the allegation against more types of suffering-focused views or ideas than is warranted. For example, the idea that there are no goods does not in itself imply anything about what is morally right or what should be done. These are different topics. One can hold that there are no goods and that it is morally wrong to destroy anything, and then destruction would, obviously, be wrong.

Even if we only talk about which scenario would be best (a matter of axiology), as opposed to what anyone should do, it is still not the case that destruction must be the best scenario if there are no goods. For instance, one can hold that being destroyed is bad for those who are destroyed, or that the act of destroying (or an associated motive or trait) has final disvalue.39 On such views, it could be better to peacefully and voluntarily get rid of suffering and other bads without any destruction.

As a final example, moral views of the kinds we mentioned above that include other moral considerations besides consequences can include rules and rights that speak against or prohibit destruction.40

4.2 Pro-death

A related misunderstanding about suffering-focused views is that they must favour the death of individuals.41 There are several reasons why this is generally not the case.

First, even if we assume that there is no positive final value and assume a strong negative utilitarian view focused only on minimising experiential suffering, death would make things overall worse when an individual life has sufficiently beneficial effects in terms of reducing suffering for others.42 In this way, staying alive would be supported by the positive roles we serve for others.43

Second, suffering-focused views that contain theories of welfare that go beyond experiences may imply that death is bad for an individual, even if the views hold that nothing can be good for individuals. For example, a theory of welfare that takes preferences into account may imply that death is bad for an individual, provided that the individual prefers to stay alive.44 Similarly, one may hold that death harms us because it violates a fundamental interest in continuing to live, or because it curtails our life projects, or simply because death is a harm in itself.45

Third, various suffering-focused views that grant the existence of positive welfare can favour continued existence for the being’s own sake because of the positive welfare they would enjoy in the remainder of their life.

Of course, there can be circumstances in which death would be less bad than the alternatives according to suffering-focused views. For example, many suffering-focused views would see death as less bad than continued existence when a person has an agonising terminal illness and wants to die, and their death would not harm others. Yet conclusions of this kind are not unique to suffering-focused views, and it seems reasonable to hold that there are some circumstances in which death is the lesser evil. To be sure, compared to other views, some suffering-focused views may be more inclined to see death as the lesser evil in particular situations. However, a lot will depend on the details, both of the specific view and the specific circumstances under consideration.46

5. On objections to suffering-focused views

The following are two ways of looking at debates and objections in ethics. First, ethics has similarities with politics in that both concern values, and people care about the issues and often want to influence things. In this vein, one can pay attention to advocacy, misinformation, money, power, rhetoric, talking points, and so on. That is interesting and something to be aware of, but we will set it aside here. Second, one can pay attention only to the content of ideas, arguments, and the like, and how to think about that content. That is the topic of the rest of this section.

There is a large web of objections and replies related to suffering-focused ethics.47 This should be unsurprising given the diversity of views and ideas. Additionally, there can be several objections against a single view or idea, and then replies to those objections, and so on.48

How are we to approach such a system of objections and replies? It can be laboursome to wade through it all, but there is seemingly no shortcut that replaces thinking through objections and replies. A critical attitude is key. One can ask oneself: Is that convincing? Does that seem reasonable?

In our experience, when one is beginning to think about a field, or if one is pressed for time, it can happen that one just takes whatever is said by experts at face value. Of course, it is often appropriate to defer to the views of experts. Yet it is worth being aware of how individual intuitions and judgements about values tend to play a large role in moral philosophy, which means that one cannot simply trust expert judgements as though they will necessarily reflect one’s own considered judgements. Thinking things through for oneself with a critical attitude may thus be especially important in ethics compared to other fields.49

To avoid going into too much detail here, we limit ourselves to a brief discussion of two kinds of objections that tend to recur in different variants. Both kinds of objections have a structure that is very common in moral philosophy, namely to allege that the target view has a problematic implication.

5.1 Placing too much importance on suffering when choosing outcomes

The first common kind of objection is to present a choice between two outcomes or worlds, and claim that the suffering-focused view under consideration prescribes the wrong choice. Here is an example from Hurka (2010, p. 200):

negative utilitarianism implies that if we could either bring about a world in which billions of people are ecstatically happy but one person suffers a brief toothache or bring about nothing, we should bring about nothing.

Hurka calls this implication “absurd”. He talks about a specific form of strong negative utilitarianism and a brief toothache, but there are different versions of the objection.50 For example, another version might be that in one of two new worlds that could be created, there are five people with positive welfare for each miserable person, and in the other there are no people. The objection would then allege that the suffering-focused view prescribes the wrong choice, namely creating the world with no people in it.

We do not find these kinds of objections to be compelling and there is a lot to say about them, but here we will merely make a couple of points to indicate some directions in which the reasoning can go.

First, a key issue is, of course, which of the outcomes should be chosen. For example, one can argue that the outcome with suffering should not be chosen for the reasons we mentioned in Section 3. In addition, one can question the judgements about which outcome should be chosen by arguing that the judgements are biased or too uninformed (of course, such arguments can be made in both directions).51

Second, one can argue that competing theories have worse implications in such abstract choice situations, and that the balance of arguments (of this kind) therefore overall supports suffering-focused views.52

Third, one can question what such abstract, hypothetical choice situations tell us about morality and what our priorities should be in the real world. In reality, we cannot readily create worlds like that, and real-world efforts to create populations with such surpluses of purportedly good lives would involve serious risks and opportunity costs (e.g. we could instead try to reduce extreme suffering and prevent much worse outcomes). Those making the objections might say that such hypothetical choice situations are still an important test of moral theories, but that is debatable.53

An informed evaluation of this kind of objection would ideally take many considerations like these into account, and would involve going through such considerations and arguments in a fair-minded way back and forth.

5.2 World destruction

Another objection (or group of objections) concerns world destruction, and it is often directed against stronger forms of negative utilitarianism.54 We earlier dealt with world destruction as a basic misunderstanding of suffering-focused views and ideas more broadly, and we now deal with it as an objection that one could coherently raise against certain suffering-focused views. In the literature, the objection is rarely as precisely formulated as one would wish. But let us assume that the target is the following version of negative utilitarianism:

Strong negative total act-utilitarianism: An act is right if and only if it results in a sum of negative well-being that is at least as small as that resulting from any other available act.55

And let us assume the following brief version of the objection:

Suppose that someone could kill all sentient beings on Earth painlessly. Strong negative total act-utilitarianism implies that it would be right to do so. But doing so would not be right, so strong negative total act-utilitarianism is false.56

We can immediately note that the objection has several parts that can all be analysed and debated. Does strong negative total act-utilitarianism really imply that carrying out this act would be right? In particular, does the act result in a sum of negative well-being that is at least as small as that resulting from any other available act?57 Would the act not be right? Even if the theory has this implication and it would not be right, what should we make of that? Does that mean that we should reject the theory, or is it merely a disadvantage of the theory, although the theory can still, all things considered, be better than competing theories?58

Likewise, even if the objection succeeds in establishing that the theory is incorrect or implausible, what would that say about which alternative theories or views to favour instead? For example, it would not imply that positive value exists and can outweigh extreme suffering, and it would not be a blow to the whole group of suffering-focused views. After all, there are many other suffering-focused views, including strong ones, that would not prescribe destruction. Rather, if the objection showed that strong negative total act-utilitarianism is implausible, that would merely demonstrate that this particular theory does not belong on the list of plausible suffering-focused views.

In addition, if the world destruction objection succeeds against a given form of negative utilitarianism, this would bode poorly for similar views that are not suffering-focused. For instance, traditional total utilitarian views (which prescribe maximising the sum of positive minus negative welfare) seem at least as vulnerable to this type of objection. Indeed, such views would arguably have worse corresponding (alleged) implications, such as killing everyone in ways that cause extreme suffering for the sake of creating greater positive welfare.59 It is therefore questionable to argue that the world destruction objection against negative utilitarianism is a reason to favour similar views that are not suffering-focused, such as traditional utilitarian views.

6. Priorities from a suffering-focused perspective

Different suffering-focused views may imply different priorities. For example, some suffering-focused views might imply that we should mostly reduce suffering in our immediate vicinity, such as in our closest relations and community. However, in this brief section, we will focus on priorities that tend to follow from suffering-focused views that are more impartial (the categories we present below sometimes overlap).

6.1 Reducing risks of worst-case outcomes

If a suffering-focused view is sensitive to the scale of suffering, and if it is combined with the empirical belief that risks of astronomical suffering (s-risks) are the largest source of suffering in expectation, reducing these risks will tend to be a key priority.60 This might in turn imply efforts to raise attention about these risks, as well as pursuing concrete policies that are likely to reduce s-risks.61

6.2 Reducing the suffering of non-human animals

Billions of non-human animals suffer severely in factory farms and slaughterhouses, and many more suffer in the wild. Views that are sensitive to the number of suffering beings will therefore generally give a high priority to reducing the suffering of non-human animals. In particular, such views will tend to support efforts to reduce and ultimately eliminate humanity’s exploitation of non-human animals, along with efforts to reduce the suffering of wild animals.62

6.3 Reducing the suffering of the worst-off humans

When it comes to human suffering, many suffering-focused views would direct our focus to the people who endure the worst kinds of suffering. For example, in our view, society should be more dedicated to alleviating and preventing the most extreme forms of human suffering due to, for instance, the worst violence, accidents, and health conditions.63

6.4 Reducing suffering in everyday life

Another implication of many suffering-focused views is to try to reduce suffering in everyday life. This might include helping people around us who are in distress; trying to cause less harm to small beings, such as insects; and making consumption choices aimed at causing less suffering, such as by avoiding animal-derived products. These practices may have a consequentialist justification based on, for example, the broader consequences of reinforcing certain norms and consistently being the kind of person who tries to reduce suffering.64 Alternatively, or in addition, these practices may rest on non-consequentialist ideas about, for example, which actions are called for and the kind of person one should be.65

A final remark on priorities is that one need not choose between reducing s-risks, suffering among non-human animals, and suffering among humans. We have presented those priorities separately, but some changes could benefit all of these areas simultaneously. For example, if society had closer to what we consider to be the appropriate concern for severe suffering, then that could broadly benefit suffering humans, non-human animals, and future beings.66

7. Conclusion

As we have seen, there is a broad range of suffering-focused views, as well as a variety of ideas and arguments that pertain to such views. While suffering-focused views differ in many respects, they all agree that the reduction of suffering is of key importance. In that regard, they tend to provide substantive and, in our view, reasonable practical directions.67

References

Ajantaival, T. (2021a). Positive roles of life and experience in suffering-focused ethics. Ungated

Ajantaival, T. (2021b). Minimalist axiologies and positive lives. Ungated

Ajantaival, T. (2022a). Peacefulness, nonviolence, and experientialist minimalism. Ungated

Ajantaival, T. (2022b). Minimalist extended very repugnant conclusions are the least repugnant. Ungated

Ajantaival, T. (2023a). Minimalist views of wellbeing. Ungated

Ajantaival, T. (2023b). Varieties of minimalist moral views: Against absurd acts. Ungated

Althaus, D. & Gloor, L. (2016) Reducing Risks of Astronomical Suffering: A Neglected Priority. Ungated

Anonymous. (2015). Negative Utilitarianism FAQ. Ungated

Arrhenius, G. & Bykvist, K. (1995). Future Generations and Interpersonal Compensations Moral Aspects of Energy Use. Uppsala Prints and Preprints in Philosophy, 21. Ungated

Baumann, T. (2017). S-risks: An introduction. Ungated

Baumann, T. (2022a). Avoiding the Worst: How to Avoid a Moral Catastrophe. Ungated

Baumann, T. (2022b). Career advice for reducing suffering. Ungated

Benatar, D. (2006). Better Never to Have Been: The Harm of Coming into Existence. Oxford University Press.

Bergström, L. (1978/2022). The consequences of pessimism. Ungated

Bommarito, N. (n.d.). Tibetan Philosophy. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Ungated

Breyer, D. (2015). The Cessation of Suffering and Buddhist Axiology. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 22: 533–560. Ungated

Calder, T. (2022). The Concept of Evil. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2022 Edition). Ungated

Chao, R. (2012). Negative Average Preference Utilitarianism. Journal of Philosophy of Life, 2(1): 55–66. Ungated

Crisp, R. (2022). Pessimism about the Future. Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 46: 373–385. Ungated.

DiGiovanni, A. (2023). Beginner’s guide to reducing s-risks. Ungated

Edelglass, W. (2009). The Bodhisattva Path: Śāntideva’s Bodhicaryāvatāra. In Edelglass, W. & Garfield, J. (eds.), Buddhist Philosophy: Essential Readings. Oxford University Press. Ungated

Elster, J. (2011). How Outlandish Can Imaginary Cases Be? Journal of Applied Philosophy, 28(3): 241–258. Ungated

Enoch, D. (forthcoming). Politics and suffering. Analytic Philosophy. Ungated

Faria, C. (2022). Animal Ethics in the Wild: Wild Animal Suffering and Intervention in Nature. Cambridge University Press.

Fehige, C. (1998). A pareto principle for possible people. In Fehige, C. & Wessels U. (eds.), Preferences. Walter de Gruyter. Ungated

Geinster, D. (1998). Negative Utilitarianism – A Manifesto. Ungated

Gómez-Emilsson, A. & Thisdell, R. (2021). A Conversation with Roger Thisdell about Classical Enlightenment and Valence Structuralism. Ungated

Griffin, J. (1979). Is Unhappiness Morally More Important Than Happiness? Philosophical Quarterly, 29: 47–55.

Gustafsson, J. (2023). Against Negative Utilitarianism (draft). Ungated

Häyry, M. (2024). Exit Duty Generator. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 33(2): 217–231. Ungated

Hedenius, I. (1955). Fyra Dygder. Albert Bonniers Förlag. [In Swedish.]

Horta, O. (2022). Making a Stand for Animals. Routledge.

Horta, O. & Teran, D. (2023). Reducing Wild Animal Suffering Effectively: Why Impracticability and Normative Objections Fail Against the Most Promising Ways of Helping Wild Animals. Ethics, Policy & Environment, 26(1): 1–14. Ungated

Hurka, T. (2010). Asymmetries in Value. Noûs, 44(2): 199–223.

John, T. & Sebo, J. (2020). Consequentialism and Nonhuman Animals. In Portmore, D. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Consequentialism. Oxford University Press. Ungated

Khyentse, D. (2007). The Heart of Compassion: The Thirty-seven Verses on the Practice of a Bodhisattva. Shambhala.

Knutsson, S. (2015a). The ‘Asymmetry’ and extinction thought experiments. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2015b). The Seriousness of Suffering: Supplement. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2016). What is the difference between weak negative and non-negative ethical views? Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2017). Reply to Shulman’s “Are Pain and Pleasure Equally Energy-Efficient?” Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2019). Lars Bergström on pessimism, ethics, consequentialism, Ingemar Hedenius, and quantifying well-being. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2021). The world destruction argument. Inquiry, 64(10): 1004–1023. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2022a). Undisturbedness as the hedonic ceiling (draft). Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2022b). Pessimism about the value of the future and the welfare of present and future beings based on their acts and traits (draft). Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2023). My moral view: Reducing suffering, ‘how to be’ as fundamental to morality, no positive value, cons of grand theory, and more. Ungated

Knutsson, S. (2024). Answers in population ethics were published long ago (draft). Ungated

Knutsson, S. & Munthe, C. (2017). A Virtue of Precaution Regarding the Moral Status of Animals with Uncertain Sentience. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 30(2): 213–224. Ungated

Knutsson, S. & Thisdell, R. (2023). Roger Thisdell on undisturbedness, positive experiences, and the hedonic peak. Ungated

Kupfer, J. (2011). When the Badness of Vice Outweighs the Goodness of Virtue: A Moral Asymmetry. Journal of Value Inquiry, 45(4): 433–441.

Leighton, J. (2018). Ending the Agony: Access to Morphine As an Ethical and Human Rights Imperative. Ungated

Leighton, J. (2020). Legalising Access to Psilocybin to End the Agony of Cluster Headaches. Ungated

Leighton, J. (2023a). The Tango of Ethics: Intuition, Rationality and the Prevention of Suffering. Imprint Academic.

Leighton, J. (2023b). Unexpected Value: Prioritising the Urgency of Suffering. Ungated.

Leslie, J. (1983). Why Not Let Life Become Extinct? Philosophy, 58(225): 329–338.

Mayerfeld, J. (1996). The Moral Asymmetry of Happiness and Suffering. Southern Journal of Philosophy, 34(3): 317–338.

Mayerfeld, J. (1999). Suffering and Moral Responsibility. Oxford University Press.

Mayerfeld, J. (2016). The Promise of Human Rights: Constitutional Government, Democratic Legitimacy, and International Law. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mendola, J. (2006). Goodness and Justice: A Consequentialist Moral Theory. Cambridge University Press.

Nobis, N. (2002). Vegetarianism and Virtue: Does Consequentialism Demand Too Little? Social Theory and Practice, 28(1): 135–156. Ungated

O’Brien, G. (2022). Directed Panspermia, Wild Animal Suffering, and the Ethics of World-Creation. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 39(1): 87–102.

Ohlsson, R. (1979). The Moral Import of Evil: On Counterbalancing Death, Suffering, and Degradation. PhD diss., Stockholm University.

Pearce, D. (1995). The Hedonistic Imperative. Ungated

Popper, K. (1945/2020). The Open Society and Its Enemies. Princeton University Press.

Popper, K. (1963/2002). Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge.

Rabinowicz, W. & Rønnow-Rasmussen, T. (2000). A Distinction in Value: Intrinsic and for its Own Sake. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 100(1): 33–51. Ungated

Ryder, R. (2001). Painism: A Modern Morality. Centaur.

Ryder, R. (2023). Speciesism and Painism: Some Further Thoughts. Etyka. Ungated

Shantideva. (ca. 700/2006). The Way of the Bodhisattva. Shambhala. Ungated

Sharma, A. (1999). The Purusārthas: An Axiological Exploration of Hinduism. Journal of Religious Ethics, 27(2): 223–256.

Sherman, T. (2017). Epicureanism: An Ancient Guide to Modern Wellbeing. MPhil diss., University of Exeter. Ungated

Shulman, C. (2012). Are pain and pleasure equally energy-efficient? Ungated

Smart, R. N. (1958). Negative Utilitarianism. Mind, 67(268): 542–543. Ungated

Tännsjö, T. (2015). Utilitarianism or Prioritarianism? Utilitas, 27(2): 240–250.

Tomasik, B. (2006). On the Seriousness of Suffering. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2011). Risks of Astronomical Future Suffering. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2013a). Three Types of Negative Utilitarianism. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2013b). Applied Welfare Biology and Why Wild-Animal Advocates Should Focus on Not Spreading Nature. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2013c). Omelas and Space Colonization. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2015a). Are Happiness and Suffering Symmetric? Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2015b). The Importance of Wild-Animal Suffering. Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism, 3(2): 133–152. Ungated

Tomasik, B. (2016). Preventing Extreme Suffering Has Moral Priority. Ungated

Tranöy, K. (1967). Asymmetries in ethics: On the structure of a general theory of ethics. Inquiry, 10: 351–372.

van den Berg, F. (2018). Victims as the central focus of ethics: The priority of ameliorating suffering over maximizing happiness. Think, 17(49): 81–85. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2020a). Suffering-Focused Ethics: Defense and Implications. Ratio Ethica. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2020b). On purported positive goods “outweighing” suffering. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2020c). Suffering and happiness: Morally symmetric or orthogonal? Ungated

Vinding, M. (2020d). Underappreciated consequentialist reasons to avoid consuming animal products. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2021). Comparing repugnant conclusions: Response to the “near-perfect paradise vs. small hell” objection. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022a). Reasoned Politics. Ratio Ethica. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022b). Some pitfalls of utilitarianism. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022c). Four reasons to help nearby insects even if your main priority is to reduce s-risks. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022d). Comments on Mogensen’s “The weight of suffering”. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022e). Reply to the “evolutionary asymmetry objection” against suffering-focused ethics. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022f). A thought experiment that questions the moral importance of creating happy lives. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022g). Reply to Chappell’s “Rethinking the Asymmetry”. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022h). Point-by-point critique of Ord’s “Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian”. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022i). Reply to Gustafsson’s “Against Negative Utilitarianism”. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2022j). A phenomenological argument against a positive counterpart to suffering. Ungated

Vinding, M. (2023). A Gödelesque argument against being a pure consequentialist. Ungated

Vinding, M. (forthcoming). Compassionate Purpose: Personal Inspiration for a Better World. Ungated draft chapters

Wolf, C. (1996). Social Choice and Normative Population Theory: A Person Affecting Solution to Parfit’s Mere Addition Paradox. Philosophical Studies, 81: 263–282. Ungated

Wolf, C. (1997). Person-Affecting Utilitarianism and Population Policy. In Heller, J. & Fotion, N. (eds.), Contingent Future Persons. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Ungated

Wolf, C. (2004). O Repugnance, Where Is Thy Sting? In Tännsjö, T. & Ryberg, J. (eds.), The Repugnant Conclusion. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Ungated

Notes

- The following are some alternative, sensible characterisations of suffering-focused ethical views: Such views give a prominent, top, or special priority to the reduction of suffering. According to these views, it is important to reduce suffering, and this consideration is particularly weighty compared to other ethical considerations. What is suffering? Different authors have different notions of suffering. One key notion is that suffering is something we experience (e.g. an excruciating mental state), and this is the notion that we mainly have in mind in this essay. But some say that suffering need not be experienced, and some use the term ‘suffering’ broadly for ill-being or whatever makes life go badly. In this essay, we sometimes deal with harm, ill-being, and what is bad for individuals, even if it goes beyond experiences.[↩]

- We talk about “views” for brevity, but more generally, we can sort ethical views, theories, principles, ways of being, and so on according to how focused they are on reducing suffering.[↩]

- This does not exhaust the diversity of possible views. For instance, another dimension along which moral views can vary is egoism versus concern for others. One can imagine a suffering-focused ethical egoism that says that I should mainly reduce my own suffering.[↩]

- See e.g. Bommarito (n.d., sec. 3a) and Breyer (2015). For examples of views within Hinduism that appear suffering-focused, see Sharma (1999, sec. 4.1).[↩]

- Shantideva (ca. 700/2006, ch. 8, verse 103); see also verses 7–10 in ch. 3, verses 91–105 in ch. 8, verses 162–164 in ch. 9, verse 55 in ch. 10, as well as Edelglass (2009). Another relevant and influential source in the Mahayana tradition is Tokmé Zangpo’s 14th-century text The Thirty-Seven Verses on the Practice of a Bodhisattva (Khyentse 2007, pp. 27–37), which in its final verse concludes: “To remove the suffering of numberless beings, is the practice of a bodhisattva.” (A bodhisattva can roughly be understood as the ideal person within Mahayana Buddhism, see e.g. Bommarito n.d., sec. 3ai.) See also verse 10 (Khyentse 2007, p. 30).[↩]

- Strong in the sense that only the reduction of suffering or ill-being matters; there is no moral role for any positive well-being.[↩]

- Pearce (1995, sec. 2.7); Geinster (1998); Chao (2012); Tomasik (2013a; 2015a); Anonymous (2015); Ajantaival (2022a). David Pearce clarifies that his view is a strong negative utilitarianism, according to which positive happiness exists, but morality is exclusively about reducing suffering, and there is no moral obligation to increase happiness de novo (email to Magnus Vinding, July 12, 2024). Other views similar to negative utilitarianism have been defended independently by Richard Ryder and Joseph Mendola, who each describe their respective views as consequentialist, but they explicitly do not aggregate suffering across individuals. Instead, they give absolute priority to the worst-off. For example, Ryder (2001, p. 65) writes that “pain, broadly defined to include all forms of suffering, is the only evil. All other moral objectives are means to reducing pain…. Of primary concern are those who suffer most – the maximum sufferers. Moral significance is not measured by the quantity of individuals affected by an action but by the degree of pain suffered by the maximum sufferers.” He later wrote about his view (painism) that “Painism is consequentialist” (Ryder 2023, p. 8). See also Mendola (2006).[↩]

- See Knutsson (2016) for more on weak negative views. An example of a philosopher who seemingly had such a view is Ingemar Hedenius (1955). We do not aim to give an authoritative interpretation of Hedenius here, but the view that he was most sympathetic to seems to be a form of negative consequentialism, according to which positive final value matters but there is some misery (or evil) that cannot be counterbalanced by any goods. For more on Hedenius, see e.g. Knutsson (2019). A more recent relevant contribution on weak negative views is Arrhenius & Bykvist (1995, pp. 50–60, 115–122) proposing a “Weak Unequal-weighted Negativism”. For an explanation of what final value is, see Rabinowicz & Rønnow-Rasmussen (2000).[↩]

- Wolf (1996, p. 278; 1997, secs. VI, VIII; 2004); Mayerfeld (1996; 1999, pp. 93, 117, 122–123, 161; 2016, pp. 22–23). For instance, Mayerfeld defends a duty to relieve suffering that may be overridden by rival moral considerations (1999, pp. 8–9). He argues that we have different fundamental interests, such as avoiding disease, torture, and untimely death, as well as a fundamental interest in autonomy. According to Mayerfeld, these fundamental interests ground human rights (2016, pp. 14, 22–23). In addition, he argues that the prevention of suffering generally deserves special priority, and he defends a substantial moral asymmetry between happiness and suffering. For example, he writes (1999, p. 178): “The lifelong bliss of many people, no matter how many, cannot justify our allowing the lifelong torture of one.” See also Häyry (2024).[↩]

- Knutsson (2023). Relatedly, Wolf (1997, p. 114) and Mayerfeld (1999, p. 85) talk about virtue and vice. Other suffering-focused views that give great importance to consequences, yet which diverge from standard pure consequentialism in some respects, are presented in Popper (1945, p. 442; pp. 548–549, 602); Leighton (2023a, ch. 11); Vinding (2023).[↩]

- We are speaking of his Principle of Unacceptable Tradeoffs, which reads as follows (Ohlsson 1979, p. 76): “The wrongness of killing another human being or causing him unbearable suffering or degradation cannot be outweighed by positive consequences befalling persons whose lives would be acceptable at all events. The wrongness of not saving another human being from death or unbearable suffering or degradation cannot be outweighed by positive consequences befalling persons whose lives would be acceptable at all events.”[↩]

- Ohlsson (1979, pp. 98–99, 114). To be precise, he proposes that “some version of” this principle has this central role (p. 114).[↩]

- Karl Popper seemed to hold roughly such a view of the centrality of reducing suffering in public policy. Popper endorsed a firm and general moral asymmetry between happiness and suffering (1945, pp. 548–549, 602), yet he seemed to consider the reduction of suffering a particularly high priority in the realm of politics. For example, he wrote (1963, p. 485): “it is my thesis that human misery is the most urgent problem of a rational public policy and that happiness is not such a problem”; and (1945, p. 442): “the fight against suffering must be considered a duty, while the right to care for the happiness of others must be considered a privilege confined to the close circle of their friends. … Pain, suffering, injustice, and their prevention, these are the eternal problems of public morals, the ‘agenda’ of public policy …” (For more on Popper’s view of the importance of suffering, see Vinding 2022h, secs. 4, 6.) A similar view has been defended by David Enoch, who argues that, in the realm of politics, other moral considerations are almost always outweighed by the importance of preventing serious suffering (Enoch, forthcoming, sec. 2). For other sources that have defended similar priorities, see Vinding (2022a, sec. 7.3).[↩]

- Fehige (1998); Sherman (2017); Knutsson (2022a); Ajantaival (2023a). For additional suffering-focused views and further information, see e.g. the following freely available texts: Vinding (2020a, part I; 2022a, secs. 7.1–7.3); Knutsson (2022a, sec. 1); Ajantaival (2023b). See also Crisp (2022) on counterbalancing extreme suffering.[↩]

- Learning about real-life instances of extreme suffering can arguably give a better (though still very faint) sense of how bad it feels. Some instances of this kind are described or depicted in Tomasik (2006; 2016); Knutsson (2015b); Vinding (2020a, ch. 4).[↩]

- One could take such judgements, consent, and involuntariness to only be morally relevant insofar as they shape the experience. For example, one can hold that involuntary suffering generally feels worse than voluntary suffering because the experience is different. Alternatively, one can consider the victim’s judgement, consent, and involuntariness to be morally relevant in themselves, beyond the extent to which they shape the victim’s experience.[↩]

- Tomasik (2015a); Vinding (2020a, ch. 4); Knutsson (2023, sec. 7.3).[↩]

- It is problematic to invoke hypothetical acceptance, consent, or judgement (e.g. the being allegedly would have judged that their suffering can be counterbalanced by purported goods) as a reason for giving lesser importance to the suffering. Some of the reasons this is problematic include (a) the being did not consent— the hypothetical consent is merely hypothetical; (b) sometimes the being could not consent even hypothetically (e.g. if the being is a certain animal) in the sense that the being would have to be radically different to be able to make the judgements in question; and (c) if the hypothetical consent is claimed to occur at a different time from the moment when the severe suffering is experienced, then it would be a different person-moment approving the severe suffering of another person-moment.[↩]

- This subsection focuses mainly on the moral importance of preventing severe suffering versus creating purported goods. It does not focus on the preservation of purported goods. One reason for this focus is that, in our view, it seems less clear whether (what might seem like) the preservation of purported goods is really a matter of preserving goods, as opposed to being a matter of avoiding certain bads, such as the suffering, deprivation, or frustrated preferences that would result from the non-preservation of the purported goods in question (see e.g. Fehige 1998; Ajantaival 2023a). Another reason for this focus is that the question about the comparative importance of creating purported goods seems far more practically relevant than the corresponding question about the preservation of purported goods (cf. Tomasik 2013c; Vinding 2020a, sec. 14.3).[↩]

- In addition to cases of ongoing suffering, one can consider real and hypothetical cases of preventing future extreme suffering, which also seems urgent when taking action earlier would prevent more future suffering.[↩]

- We here assume, for the sake of argument, that it is possible to create beings with positive welfare, although we will disagree with that assumption in the next subsection.[↩]

- For more on urgency, see Vinding (2020a, sec. 1.4); Leighton (2023a, ch. 4; 2023b).[↩]

- On evil, including monstrous evil, see Calder (2022).[↩]

- We are talking about the isolated phenomenon of not creating purported goods. In contrast, if not creating purported goods would result in disappointment, a damaging lack, or the breaking of a promise, then that would be a different matter.[↩]

- See van den Berg (2018) for a suffering-focused view that emphasises victims.[↩]

- The phrase ‘morally worth preventing’ is unspecific. How would it be prevented? What we mean is that the balance of severe suffering and purported goods in the outcome speaks in favour of avoiding that outcome, although there can be other moral considerations, such as respecting autonomy, that bear on what someone should do, all things considered. [↩]

- See Vinding (2020a, sec. 6.7) for relevant ideas related to contractualism, although we do not rely on that theory.[↩]

- A similar view has been expressed by Ingemar Hedenius (see Bergström 1978/2022). See also Vinding (2020b); Ajantaival (2023a, sec. 2).[↩]

- Vinding (2020a, sec. 1.4; 2020b; 2020c). Others who defend a moral primacy of reducing suffering over increasing positive value or well-being include Tranöy (1967, p. 359); Wolf (1997); van den Berg (2018); Leighton (2023a, ch. 4; 2023b).[↩]

- This is not to be confused with the claim that there is no positive instrumental value, cf. Ajantaival (2021a; 2021b); Vinding (forthcoming, sec. 6.3).[↩]

- A way in which our suffering-focused views do not hinge on the non-existence of positive final value was outlined in the previous subsection. We think that the reasons and arguments outlined there stand even if there is such a thing as positive final value. See also Wolf (1997); Vinding (2020a, sec. 1.4; 2020b; 2020c).[↩]

- Instead of flawless versus flawed, we could also speak in terms of unproblematic versus problematic or perfect versus imperfect. Note that we use the terms ‘quality of life’, ‘welfare’, and ‘well-being’ more or less interchangeably.[↩]

- For a related idea about virtue and vice, see Kupfer (2011).[↩]

- The figure is about quality of life, but one could create a similar figure where ‘quality of life’ is replaced with, for example, ‘quality of experiences’.[↩]

- The ‘flawless’ line in the figure need not imply much in terms of whether a life is worth continuing or not because discontinuing it could be worse than continuing it, both for oneself and others.[↩]

- Similarly, Rogert Thisdell writes that he has experienced “bliss trips, jhanas, 5-MeO, MDMA, staring into the eyes of a lover without insecurities, laughing fits”, and he likewise holds that “pleasure as a positive, as an actual added experience, does not exist” (Gómez-Emilsson & Thisdell 2021; see also Knutsson & Thisdell 2023).[↩]

- For more information, see e.g. Knutsson (2022a); Vinding (2022j); Ajantaival (2023a) and the sources in those texts.[↩]

- See also Knutsson (2021).[↩]

- See e.g. Knutsson (2022b) and the sources found there on disvaluable acts and traits.[↩]

- See also Vinding (2022d); Ajantaival (2023b).[↩]

- The misunderstanding, as we describe it here, is unspecific. For example, it can be about what would be better or worse for an individual, what would make the world better or worse, or what we should do. What we say in this subsection is relevant to all of these alternative formulations, yet we avoid technicalities to keep the text readable.[↩]

- In fact, given how much suffering we can potentially reduce for others by staying alive and working toward this aim (and how much suffering our death can cause others), views like strong negative utilitarianism may often be much more opposed to death, and be much more demanding in terms of requiring people to stay alive, compared to what common-sense intuitions might hold.[↩]

- Vinding (2020a, sec. 8.2); Ajantaival (2021a; 2021b). On its face, it might seem like this consideration regarding beneficial effects only applies to moral agents, but it also applies to beings who may not be moral agents. For example, the death of an animal in the wild, such as a large herbivore, might overall increase suffering if this death (and the resulting greater availability of plant food for other beings) in turn leads to a larger number of smaller beings who suffer more than the large herbivore would (cf. Tomasik 2013b; Vinding 2020a, sec. 8.2). In that case, strong negative utilitarianism would favour the continued survival of the large herbivore.[↩]

- Fehige (1998); Chao (2012); Anonymous (2015).[↩]

- See e.g. Ohlsson (1979, ch. 1); Mayerfeld (1999, pp. 160–161); Benatar (2006, pp. 148–152, 211–221); Ajantaival (2023a).[↩]

- Another misunderstanding about suffering-focused views is that they necessarily imply antinatalism, or vice versa (here we simply take antinatalism to be the view that it is morally wrong to have children; the term is sometimes defined in other ways). Yet while suffering-focused views and antinatalism can be related, they are distinct and need not imply each other. Certainly, one could endorse antinatalism based on a suffering-focused view. For example, one could favour antinatalism based on concern for the suffering that the new being would experience, or based on the argument that we can better reduce suffering in other ways than by creating new beings. However, one could also be an antinatalist without endorsing a suffering-focused view. For example, one could be an antinatalist for environmental reasons. Conversely, one can endorse a suffering-focused view without endorsing antinatalism, such as due to the positive roles that new lives may have for others (Ajantaival 2021b).[↩]

- Some of them can be found in Knutsson (2024, notes 21–22). In addition, the following four publications provide a window into how philosophers have argued against various suffering-focused views since the 1970s: Griffin (1979); Leslie (1983); Arrhenius & Bykvist (1995, pp. 31–42, 115–117); and Tännsjö (2015). To be clear, Arrhenius and Bykvist argue against some suffering-focused views, but they also write “we believe that unhappiness and suffering have greater weight than happiness” (p. 20), “we revealed ourselves as members of the negative utilitarian family” (p. 115), and “It is not true that any suffering can be compensated by happiness” (p. 115). Some objections are also brought up and replied to in Vinding (2020a, ch. 8; 2022h).[↩]

- In addition, there are replies and points that people have not taken the time to publish. Sometimes the continuations of published reasoning are even obvious. So it is insufficient to limit the scope to the published literature.[↩]

- For more on the role of intuitions and judgements in moral philosophy, see Knutsson (2023, sec. 7.1; 2024, sec. 4).[↩]

- Gustafsson (2023) makes heavy use of choices between outcomes when arguing against negative utilitarianism, and Vinding (2022i) replies.[↩]

- An argument of this kind against suffering-focused views can be found in Shulman (2012). Replies to this text can be found in Knutsson (2017) and Vinding (2022e). For more on potential biases and confounding factors, see e.g. Knutsson (2015a) and Vinding (2020a, ch. 7; 2022f).[↩]

- Vinding (2021; 2022i); Ajantaival (2022a, sec. 2.5; 2022b).[↩]

- See e.g. Elster (2011) for background on the use of unrealistic thought experiments in moral philosophy. See also Vinding (2022g, sec. 4).[↩]

- See e.g. Smart (1958). For some critical discussion of this objection, see Knutsson (2021); Ajantaival (2022a).[↩]

- This formulation is a quote from Knutsson (2021, p. 1007).[↩]

- This version of the objection draws on Knutsson (2021, p. 1007).[↩]

- For discussion of this question, see Knutsson (2021); Ajantaival (2022a).[↩]

- We are sympathetic to the view that if a moral theory prescribes immoral behaviour, the theory should be rejected (see e.g. Knutsson 2023). But this position is not a given, and many others seem more accepting of a theory even if it has problematic implications.[↩]

- Knutsson (2021, secs. 2–3); Ajantaival (2022a, sec. 2.5).[↩]

- It will not necessarily be the main priority on these grounds alone. For example, reducing s-risks could be less tractable than other causes, in which case those other causes might be more promising to focus on.[↩]

- Tomasik (2011); Althaus & Gloor (2016); Baumann (2017; 2022a); Vinding (2020a, ch. 14; 2022a part IV); DiGiovanni (2023).[↩]

- Tomasik (2015b); Vinding (2020a, ch. 11; 2022, ch. 10); O’Brien (2022); Horta (2022); Faria (2022); Horta & Teran (2023).[↩]

- See e.g. Leighton (2018; 2020).[↩]

- Vinding (2020d; 2022b; 2022c; forthcoming, ch. 9). See also Nobis (2002); John & Sebo (2020).[↩]

- Knutsson & Munthe (2017); Knutsson (2023).[↩]

- Vinding (2020a, part II) discusses at length how to best reduce suffering, and some of the suggestions found there could be broadly beneficial for s-risks and the suffering of humans and non-humans alike. In addition, there are certain decisions, such as career choice, that deserve a high priority regardless of one’s specific priorities. Baumann (2022b) has written about career choice from a suffering-focused perspective.[↩]

- We are grateful to Teo Ajantaival, Tobias Baumann, Roger Crisp, Oscar Horta, Jonathan Leighton, Joseph Mendola, David Pearce, Mat Rozas, Brian Tomasik, and Alistair Webster for comments on earlier versions of this text. We thank Matti Häyry for helpful correspondence.[↩]